Kristen Mae

Forum Replies Created

Viewing 9 posts - 1 through 9 (of 9 total)

-

Kristen MaeParticipantWhen schools come visit us, we call them "field studies" instead of field trips to set the tone that when they come visit us they are going to be observing and studying the ecosystem we go out into. We encourage teachers to have the students bring their science notebooks and before we go into the ecosystem we pose a question: "why are fiddler crabs important to the salt marsh", "why is biodiversity important", etc and then have the students write down a hypothesis in their journals. It may be beneficial to also have them come up with their own questions and hypotheses about the ecosystems as the day progresses.in reply to: Launching Investigations #726024

-

Kristen MaeParticipantI have tried out Seek this week and enjoyed it. I think that students would also enjoy being able to identify things. One of the main questions I get while in the field is "what is that?!" However, many times phones are not allowed on field trips and if they are, they can become a problem. We also try to use the time to get away from screens completely, so I do not believe apps are something we could implement into our field studies. However, we try to send back take-home activities with the students after their field trip with us is complete. We use the activities to try and engage the parents with what the students learned and bring environmental education/stewardship into the home. I could add the download of Seek to a take-home activity and turn it into a collaboration between students and their parents: how many badges can you get before your next field study? We are always looking for ways to get parents more involved and keep a student's environmental exploration going even after they go back home.in reply to: Symbiosis in the Soil – Classroom Case Study #723568

-

Kristen MaeParticipantMy organization takes students out into the field. I have found that if the teachers are excited about going out into the field, the students feed off that excitement. On the other hand, I have sadly had teachers that have said "we're not outdoors people" and complained about being outside. This negative attitude was quickly reflected in the students as well. Even students that were initially enthusiastic and excited, changed course when they saw the reaction of their teacher. Having a curious, open-minded attitude encourages students to also have this same attitude.in reply to: Supporting Open-ended Questions #723541

-

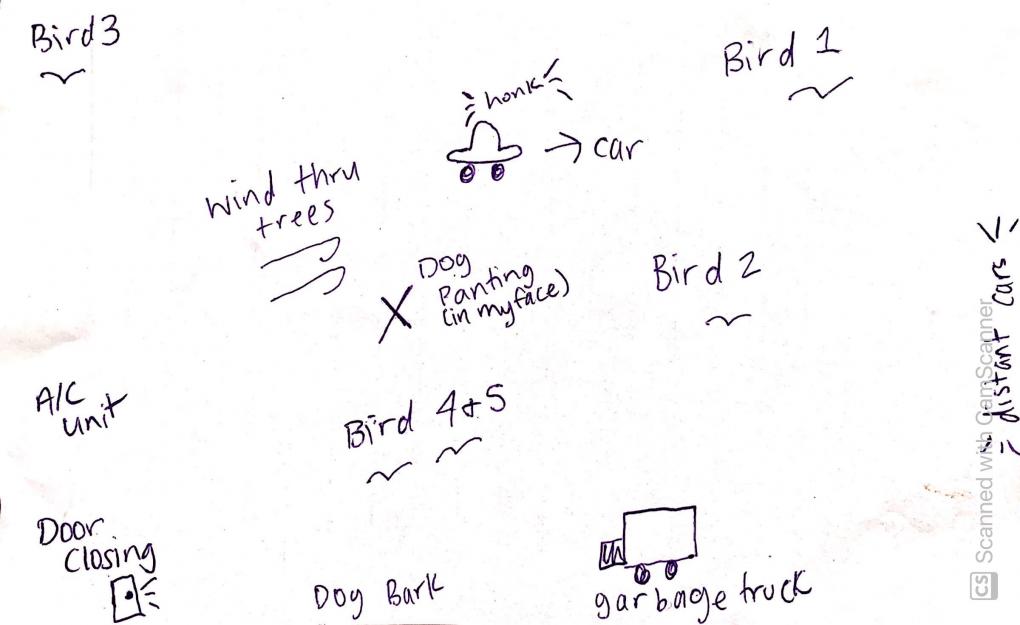

Kristen MaeParticipantOne of the main lessons we try to teach our program participants is the importance of biodiversity. When we go out into the field, students get disheartened pretty quickly when they do not see any animals or they exclaim that it's not a healthy ecosystem because we aren't seeing any animal biodiversity. At this point I usually sit them down and do a "be silent and listen" exercise for a minute. I ask them to count how many different birds, insects, or other animals they hear. They are almost always amazed to find they hear way more than one animal. I then ask if we heard every single animal that may make use of the area we are in and why. This short exercise seems to open their eyes on how much biodiversity is around them, whether they can see it or not. It reveals itself when you take a moment to stop and listen.

in reply to: Encouraging Observations #723538

in reply to: Encouraging Observations #723538 -

Kristen MaeParticipantMy organization is a support group for the area's National Forest and Wildlife Refuges. The students get the opportunity to explore and learn about these places. I would like to connect these lessons and experiences so that the students don't forget about their public lands once they leave the field trip. A goal of our environmental education programs is to inspire young students to become motivated citizens that will continue to protect our public lands. I think that citizen science and inquiry-based learning can spark this interest to want to protect the places they learned about and even take their new knowledge back home and spread it to their family and friends.in reply to: Linking Citizen Science & Inquiry #720103

-

Kristen MaeParticipantAfter I introduce myself to the students and before I take them out into the field, I always say to them "today you are the scientist." I think this encourages them to take pride in their observations. It's not just another assignment, it's their personal observations that they can use to make their own conclusions. At the end of the day we discuss what we learned about being a scientist, how did we make observations and use those to answer questions. Before they leave I remind them that when they are out investigating the world, they are always scientists. Them being a scientist does not end when they get back on the bus. I would like to find ways to incorporate citizen science lessons into my organization's current field studies. So that the students can take what they've learned during the day with me and continue it after they have returned back to their school and even their homes.in reply to: Citizen Science in Your Classroom #720102

-

Kristen MaeParticipantSince I am not consistently with my students (usually only single visits), it is sometimes hard to get them involved in citizen science. We provide resources to different citizen science projects to the teachers to encourage their participation. I would love to find ways to get kids involved for at least the short time I see them. If I can get them to be enthusiastic during their time with me, maybe they will continue participating in the project on their own.in reply to: Intro to Citizen Science #720100

-

Kristen MaeParticipantI teach environmental education at multiple schools in the area. My most involved program is Earth Stewards, a 8-lesson program that teaches students about their local national forests and wildlife refuges as well as encourages them to find ways they can help protect their natural resources. Each lesson begins with a question: why are fiddler crabs important to the salt marsh, what skull adaptations do mammals have to help them survive, how are public lands managed to help wildlife, etc. I then have activities for them to do to help them answer these questions. For example, one lesson asks: why are wetlands important to South Carolina? I tell them by the end of the day they will know 5 reasons why wetlands are important. 3 of these are revealed through the lesson, but they must figure out 2 of them during our experiment. The experiment involves sponges to represent the wetlands. The students will hopefully notice less flooding when the "sponge wetlands" are present and can deduce that wetlands are important to prevent flooding because they can soak up water. Students will also model pollution with food dye (liquid pollution) and sprinkles (solid pollution). Their "sponge wetlands" should filter out the pollution and they can deduce that wetlands are important because they prevent pollution from entering into the ocean. Each group of students gets their own wetland model to create (with guidance), so they get practice creating a model and how scientists can use models to make observations and apply their model observations to real world applications.in reply to: Inquiry in Your Classroom #720098

-

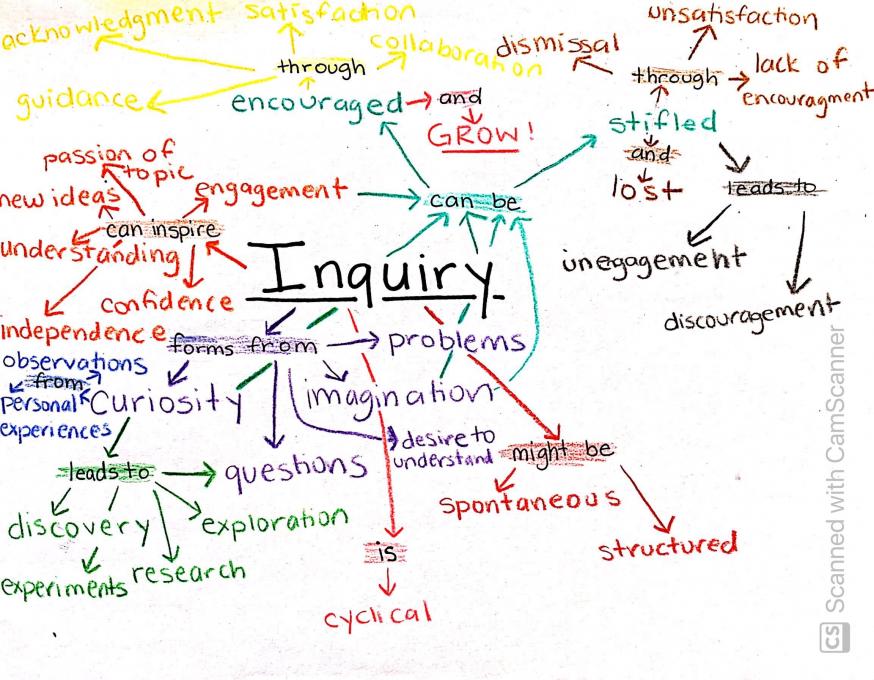

Kristen MaeParticipantWhen I think of inquiry I think of young children asking: why, why, why, why? I think this curiosity of how the world works is a natural trait of all youth. However, the reaction we receive from our many "why's" determines how many more questions we might ask in the moment and as we get older. If we're met with frustration, anger, and dismissal we may begin to lose our natural tendency toward inquiry and as we grow into middle and high school we still associate this curiosity with being annoying and uncool. But if we are instead met with encouragement, excitement and leadership, our desire for inquiry can last beyond our adolescence and well into adulthood.

in reply to: Intro to Inquiry #720093

in reply to: Intro to Inquiry #720093

Viewing 9 posts - 1 through 9 (of 9 total)