sarah

Forum Replies Created

Viewing 12 posts - 1 through 12 (of 12 total)

-

sarahParticipantSince the nature and outdoor clubs I teach are for fun and not graded, any of the citizen science projects and inquiry projects we would do would not be graded. Instead, I usually try to incentivize them with a reward for completing the project. For the most part, I plan on leaving it up to them with how well they do. They may be able to take the ideas from nature club and use them in their daily classrooms for science fair projects or other graded projects.in reply to: Sharing Student Projects #852796

-

sarahParticipantI am a new educator and haven't had a lot of experience with inquiry-based activities but I have come up with a list of challenges I could expect. The first challenge facing me is time. I'm an informal educator and I only get to see my students once a week for an hour. This makes it really hard to plan long projects or projects with multiple- time consuming portions. Another challenge is technology. All of my classes meet outside and are usually titled "nature club" or "outdoor club" the students don't want to go into the library or use computers during this limited time. This makes things like doing research or creating graphs challenging. Another challenge I face with my students is age and ability range. My students meet in a group and usually contain different grade levels, abilities, and experience. This could be a challenge for requiring in-depth inquiry projects.in reply to: Assessing Investigations – Classroom Case Study #852559

-

sarahParticipantI researched eBird. EBird is a citizen science database, used nationwide to track location, species, and abundance of birds. This database is accessible to anyone, including students and people not participating in the project. There is so much data that students could use it in a multitude of ways to conduct information. They could look at abundance of certain bird species throughout different months of the year, track trends in sightings over multiple years, look at the time of year when certain species start to migrate, they can even compare numbers found between different regions, states, countries, or habitat types.in reply to: Data Literacy Through Citizen Science #852549

-

sarahParticipantI always think that the best way to spark curiosity and questions is by starting with a blank slate. Often times, the first meetings with my group we go on a nature walk. We will stop along the way and do some activities or I will point out some cool things to them, but most of the time I let the students lead. We walk and when they see something they ask about it. I respond to their question with other questions that really get them thinking. Sometimes they will point at holes in the ground and ask "what lives there?" I'll ask them "how do we find out?" Naturally, all the other students are intrigued and gather around and start looking into the hole, guessing what could have made it by the size. Some will grab sticks and insert them to see how deep the hole is. Students are naturally curious and by stepping back, we allow them to ask questions on their own. To inspire them deeper into thinking about observational and experimental questions, I like to play games or use scenarios to really get their mind thinking. If one students says "I think a squirrel lives in that hole" I'll respond by saying "how can you find out for sure?" Asking these types of questions allows them the opportunity to think critically and be able to come up with ideas to answer their questions. They may start looking for tracks or food around.in reply to: Launching Investigations #852335

-

sarahParticipantI chose to collect data using eBird. I didn't experience any challenges because I've used this (and other citizen science portals) frequently in the past. One thing that's worth mentioning is that with any of these projects that rely on data, I always feel like I want to record everything but knowing that when I see very little observations, it's still worth recording because no data is better than wrong data. If the students participated in this projects then they would learn about bird identification and sounds, how to estimate flock numbers, where the species can be found, which species are solitary and which can be found in groups, which species can be seen in that time of year, and how fun it is to do science.in reply to: Symbiosis in the Soil – Classroom Case Study #852319

-

sarahParticipantOne of the ways to help guide students to observe and wonder is by allowing them the opportunity to see new things and places. When they are surrounded by the unfamiliar, naturally questions and wonder arise. We can also ask open ended questions which might lead them to seeking answers but also might encourage them to ask questions about other things. I think the best way is just by modeling that even teachers don't know everything and we have our own questions about things. This type of modeling makes it more comfortable for students to ask questions as well. Sometimes its best not to give students the answers but to encourage them to solve problems on their own. Another way to encourage wonder and observations is by having them come up with their own questions by giving them options of ways to observe. For example, we have two game cameras, where should we put them? Then the students can start thinking about questions they want to answer using the game cameras.in reply to: Supporting Open-ended Questions #852312

-

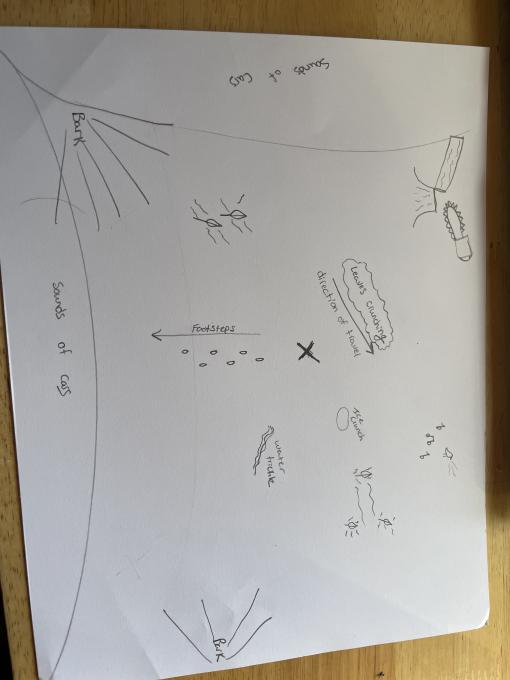

sarahParticipantFor me, the most impactful thing about creating a sound map was how the sounds of humans overwhelm the sounds of nature. Even in the woods, the noise of cars driving in the distance, airplanes overhead, and dogs barking can be heard far more common than the songs of birds, the trickling of streams, and the scampering of squirrels. Some fun activities I plan on doing with the children to observe the natural world through the use all the senses are: touch scavenger hunt, color walks, taste of the forest, and sound recordings. With the touch scavenger hunt, I have natural objects hidden in paper bags. The students reach their hands in to feel it. They describe what they feel and go touch things around the forest until they find something that feels the same way. During a color walk, students are given a sheet of colors, and they try to find as many things that match those colors as they can. When we do "A taste of the forest", we go for a foraging walk and learn about the edible things to find in the forest. The students usually get to chew on some wintergreen, dig up some Indian cucumbers, and sample maple syrup. When we do sound recordings, similar to the sound map, students close their eyes. I play recordings on my phone of animals and they listen and try to name the animals.

in reply to: Encouraging Observations #852299

in reply to: Encouraging Observations #852299 -

sarahParticipantAs a secondary educator that only sees my students once a week for an hour, some of these practices could be a challenge to incorporate into our limited time together. I think for my situation, the approaches that I look forward to using are to incorporate wonder boards, or other forms of this idea into a walk on our nature trail. Have them brainstorm questions as we walk. The most important type of science to focus on for us would be observational studies: things that we can observe during our outdoor meetings. Making reports or displays probably isn't in the cards for my groups but I think that they can still go through the process of inquiry and collecting data for projects.in reply to: Linking Citizen Science & Inquiry #851435

-

sarahParticipantThe first practice mentioned in this article was about making the students feel like they are scientists, not just helpers. I think that this is important in citizen science because students can easily fall into the trap of just repeating the steps instead of thinking critically for themselves and learning the scientific process. One way to achieve this method is by introducing them to a citizen science outlet and as they are gathering information, encourage them to ask questions about some of their observations and do some research to help them answer them. The second practice is to frame the work locally and globally. I think of pollinators as a great topic for this. The research is important because of the global decline of pollinators and we can help collect data by looking at our own community gardens and planting some native plants. The students could participate in planting the gardens and observing which species come to pollinate the flowers, this is an example of framing science both globally and locally. The third practice is harder to prepare for but equally as important as the first two: attend to the unexpected. I think that if students find things that interest them or new curiosities then that is great! Questions always mean that the students are engaging and interested. Allowing them to seek answers on anything allows for more knowledge circulation. I wish to model all of these principles by allowing students to choose what interests them, tying those questions into global and local importance and always assisting them in seeking new knowledge and answers to curiosities.in reply to: Citizen Science in Your Classroom #851422

-

sarahParticipantAlthough I haven't used any citizen science projects with my students yet, I am familiar with quite a few that I use myself. I'm a frequenter of eBird, iNaturalist, and Seek. I also participate in state level citizen science such as the Maine Bird Atlas, bumblebee atlas, and herp atlas. My goal by the end of this school year is to have each one of my nature clubs participate in a citizen science effort of their choosing. Bud Burst and the bumblebee atlas are two options that I think my students would really enjoy doing.in reply to: Intro to Citizen Science #851392

-

sarahParticipantAs a newly hired secondary educator, I don't have much experience teaching any levels of inquiry. I lead nature clubs at school where students are encouraged to explore, ask questions, and learn about the natural world. Although we don't have structured science lessons, I do teach lessons on citizen science. One of these opportunities is to collect data on bumblebees for the state atlas. I would consider this structured inquiry because the students are given the question- what bumblebees live in this meadow- and the procedure- collect as many bumblebees as you can find, identify them, and record the data. Through this activity they are developing the ability to make critical observations, learning how to identify different species, and how something fun can be used to collect important data. This lesson has so many opportunities to be more open-ended. We could go to the meadows, the students could look around, observe and come up with their own questions about flowers and pollinators. This more open-ended option would allow them to practice the scientific process from beginning to end by asking questions, developing investigation strategies, observing, and summarizing what they found.in reply to: Inquiry in Your Classroom #851089

-

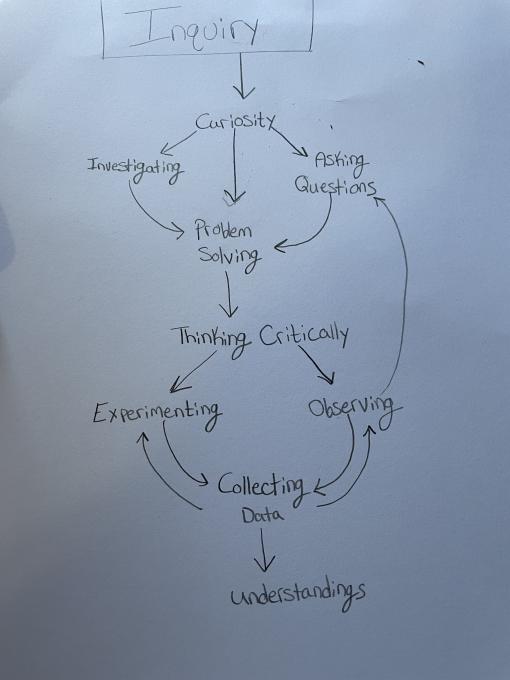

sarahParticipantInquiry is an investigative process where curiosities and questions lead to investigations, critical thinking and experimentation until questions are answered and explained by analyzing data and observations.

in reply to: Intro to Inquiry #851051

in reply to: Intro to Inquiry #851051

Viewing 12 posts - 1 through 12 (of 12 total)