How Hunters and Artists Helped Save North America’s Waterfowl

Be a part of the Duck Stamp success story

The Wood Duck (Aix sponsa) is a shimmering spectacle of color with feathers that appear to have been hand-painted by an imaginative artist. Its crested head, wings, and flanks are adorned with iridescence, set-off by crisp white lines, and tipped with a vibrant coral-hued bill and eye.

What’s more, these marvelous birds are easy to see in many hardwood bottomlands and quiet wooded ponds across North America. Careful observers may even spot adult Wood Ducks perched high in forest trees in early spring, where they nest in natural cavities—they also take readily to nest boxes. In late summer, Wood Duck nestlings fledge by the dozens from their nest cavities, hurling themselves to the ground or water far below when prompted by a special contact call from their mother.

Tara Tanaka Digiscoped Photography

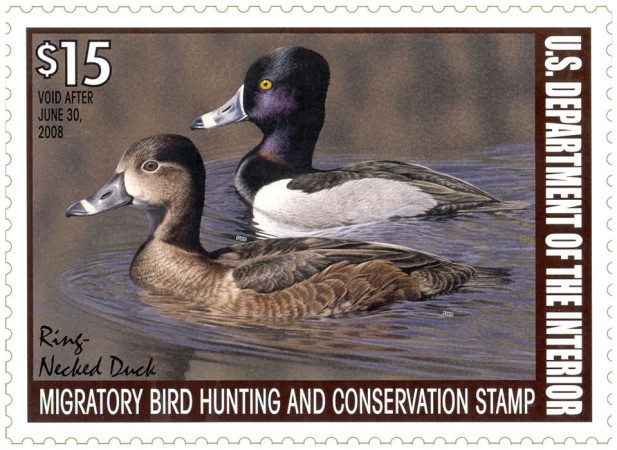

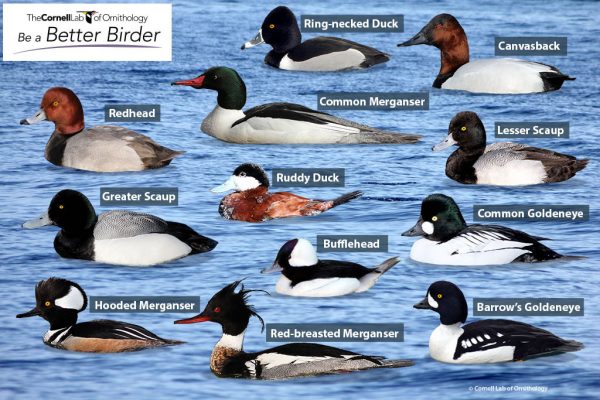

But it wasn’t always this way for Wood Ducks. In the early twentieth century, a combination of habitat loss and hunting for food, trade, and sport, had brought Wood Ducks to the verge of extinction. “Being shot at all seasons of the year, [Wood Ducks] are becoming very scarce and are likely to be exterminated before long,” remarked veteran naturalist Joseph Grinnell in 1901. In fact, overhunting had depleted numerous waterfowl populations including: Canvasbacks, Redheads, two species of scaup, goldeneye, Ring-necked Ducks, Northern Pintail, American Wigeon, Gadwall, Mallards, three species of teal, and Canada and Snow Geese and federal action was essential to their continued prosperity. The recovery of waterfowl populations was a long process full of political debate.

So how did we get back to the relatively healthy waterfowl numbers we regard as normal today? A clever federal plan called the “Duck Stamp Act” played a major role by ensuring that waterfowl hunters bought into long-term conservation and management. In so doing, the Act became a pivotal regulatory power, putting a check on unrestricted hunting while steering funds from the Act towards alleviating habitat loss. The program gained acceptance—despite its cost to hunters—by deploying alluring waterfowl stamps sourced from an art contest that soon gained national prestige. The Duck Stamp Act continues to this day to be a world-renowned conservation program. It permits anyone—hunter or not—to directly support the conservation management of critical migratory waterfowl habitats and birds. And while it has helped ducks return to safe numbers, this program cannot alone safeguard key migratory waterfowl habitats in the face of changing public priorities and continued development. To succeed, the program will need our growing population to support a healthy future for waterfowl by joining hunters in carrying the stamp and in supporting other conservation programs.

Ducks on their way to extinction

The early 1900s were hard times for the Wood Duck and all wild game birds. Critical migratory waterfowl habitats including vast hardwood bottomland forests and inland wetlands were harvested, drained, and plowed over for agriculture and to accommodate the exploding U.S. population. Hunting native birds was common and largely unrestricted. Birds were baited relentlessly and shot at close range without consideration for population numbers or season. Market hunters compounded the problem by harvesting tens of millions of wild migratory birds per year and carting them to large urban markets for food, the millinery trade, and export. In 1903, a groundbreaking book entitled Birds in Their Relation to Man highlighted the overuse: “For years professional hunters slaughtered, dealers handled, and gluttons gobbled without reason or restraint. There could be but one result: wild fowl have become scarce. Gunners no longer return at night with more birds than they can carry; not seldom they come in empty handed. But the millionaire makes up the shortage by paying higher prices. When a pair of canvas-backs bring in a five-dollar note there is still money in shooting ducks.”

A national shift in how American citizens viewed natural resources was taking place just after the turn of the century. With fresh examples of abundant species—like the American Bison and the Passenger Pigeon—pushed to extinction by unregulated hunting, it was clear that regardless of bounty, overharvesting could wipe out species. The decline of waterfowl was also contributing to this awakening.

The Migratory Bird Treaty was a critical step in the process of getting unregulated hunting of waterfowl under control. The Treaty was a conservation agreement initially signed in 1916 by Canada (then a part of Great Britain) and the United States, which promised protection for migratory waterfowl and game species that were threatened by overhunting for food, sport, or trade of parts. The Migratory Bird Treaty Act, ratified by Congress in 1918, was the first legal document in the world that made it unlawful to: “pursue, hunt, take, capture, kill, possess, sell, purchase, barter, import, export, or transport any migratory bird, or any part, nest, or egg, or any such bird, unless authorized under permit…” Mexico (1936), Japan (1972), and Russia (1978) subsequently joined the Treaty. The federal government also specifically banned the hunting of Wood Ducks in 1918. Since its passage, the Act has been modified to extend protection to non-game species and to exempt invasive species from protection. Later, the Duck Stamp Act would give teeth to the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, which remained largely symbolic without the economic support needed for enforcement.

We must be the ones to shoulder the burden and see that our thoughtlessness or selfishness does not allow us to squander that which we hold in trust.”

At the same time, habitat loss was pinching waterfowl populations too. The global demand for staples like wheat during World War I led to the draining of “prairie pothole” and ephemeral wetlands of the Great Plains. Habitats along the central U.S. flyway, which were essential to the persistence of some of the largest waterfowl migrations, simply disappeared. By the 1930s, ducks, geese and swans were down to historic lows, with estimates of around 50% of populations today. With the country now facing an apparent game shortage, the Dust Bowl, and the Great Depression, there was a dire need to develop a federal system that could manage populations according to their habitat and migratory needs.

In a 1919 editorial, the president of the American Game Protective Association said, “If young men from the next generation are to enjoy from the country’s wild life anything like the benefits derived by the present outdoor man, we must be the ones to shoulder the burden and see that our thoughtlessness or selfishness does not allow us to squander that which we hold in trust.” One captivating young leader—a fiery-spirited editorial cartoonist—took a battle stance.

Inspiring stewardship

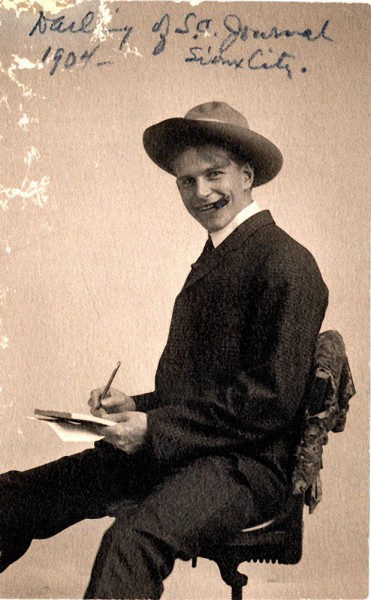

Jay N. Darling was a charged political commentator and environmentalist self-nicknamed “Ding,” who rose to fame in the mid-1920s. Ding spent much of his life working as an editorial cartoonist for the Des Moines Register in Iowa, though he also worked for the New York Herald Tribune and New York Globe. Ding won the Pulitzer Prize for Editorial Cartooning twice, once in 1924, and again in 1943.

Ding had a passion for waterfowl, hunting, and conservation of resources. Ducks took center stage in his cartoons—portrayed with anthropomorphic features and often depicted as being mistreated by humankind. Ding’s provocative cartoons prompted a deeper societal discussion about our relationship with nature, hastening a U.S. revolution in environmental ethics.

Ding was also a staunch Republican who drew scathing political cartoons about President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal policies. FDR noted Ding’s public appeal and his passion for conservation and waterfowl as he was searching for a strong leader to shape public opinion and help him move the government to restrict migratory bird hunting. Despite their political rivalry, FDR appointed Ding to an 18-month term as chief of the U.S. Biological Survey (1934-1936), predecessor to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

FDR’s bet proved fruitful. While in office, Ding had an ingenious idea: Why not enlist waterfowl hunters to become stewards of the species and habitats they rely on? This idea was visionary—born in the midst of the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl—when natural resources were increasingly scarce. In his short time working in Washington, Ding got a federal waterfowl conservation and management plan off the ground and ensured its future. Along with drafting the concept of the Duck Stamp Act and the stamp itself, he personally secured over $20 million dollars from the U.S. Treasury, used exclusively to purchase half a million acres of national refuge and restoration lands across the southeastern and western coastal U.S. He then doggedly pressured the president into setting aside another three million acres of public lands with executive orders.

Ding spent the remainder of his life as an outspoken leader in conservation. He founded the National Wildlife Federation, fought for continued funding for migratory waterfowl, and was awarded the (Theodore) Roosevelt Medal for Conservation in 1942. In political circles, he came to be known as “the best friend a duck ever had.”

How the Duck Stamp works

Ding’s vision became a reality in 1934, when Congress passed the Migratory Bird Hunting Stamp Act, more commonly known as the “Duck Stamp Act” just a few months after Ding had first proposed it. At the time, populations of North American migratory waterfowl were estimated to be at an all-time low of roughly 27 million breeding migrants (compared with about 50 million today).

The Duck Stamp Act was simple—that is why it worked. It required all waterfowl hunters 16 years of age or older to purchase a stamp and carry it along with their general game hunting license. Unlike hunting resident game species (largely managed by individual states at the time), the Duck Stamp linked stamp-generated funds to securing and managing lands prioritized for migratory waterfowl populations.

Theodore Roosevelt had established the first bird reserve to protect nongame birds in 1903 (it was just three acres). His concept grew into the present day National Wildlife Refuge system, which has been greatly augmented by the Duck Stamp. By the end of his term in 1909, there were 51 national wildlife refuges set aside in 17 states with thousands of acres protected. Today the U.S. has 562 refuges and another 209 waterfowl production areas with over 150,000,000 acres devoted to wildlife. Essentially, waterfowl hunters have become active contributors to a federal, data-based management system for their game. A federal tax on ammunition, enacted by the Pittman-Robertson Act (1937), also helped state governments manage their wildlife, giving back federal tax revenue depending on the proportion of hunters and land available.

In 1937 Wood Duck populations were recovering sluggishly even while being protected by a hunting ban, but a plan to provide nest boxes offered new hope. The pace of their recovery since the ban showed that populations weren’t just suffering from hunting; habitat loss had deprived them of the mature dead trees they required for nest cavities. As nest boxes began to appear by the hundreds, populations responded rapidly. Nesting was successful in about half of the nest boxes installed over the first two years of a pilot plan meaning hundreds more Wood Ducks were surviving each year. The box designs—attributed to biologists Gil Gigstead and Milford Smith at Chautauqua National Wildlife Refuge in central Illinois—remain central to Wood Duck management across North America. Hundreds of thousands of Wood Duck nest boxes have now been installed by private citizens and federal agencies.

Four years after the first nest boxes were installed, there were enough Wood Ducks for a limited hunting season to resume in 14 states. The first year U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service published data on the federal duck harvest (1961), Georgia hunters shot 4,100 Wood Ducks (20% of Georgia’s total waterfowl harvest). Today around 50,000 Wood Ducks are harvested in Georgia (40% of the annual state harvest). Private hunter-associated programs also provide critical support to waterfowl conservation. Ducks Unlimited, a private non-profit started by concerned sportsmen just three years after the Federal Duck Stamp Program, stands out as the world’s leader in waterfowl and wetland conservation fundraising. The program strengthens the association of hunters with conservation ethics. Thus, the combined effort of private, non-profit, and governmental programs ensured that Wood Ducks and other waterfowl populations would recover and persist. By the 1960s, Wood Ducks numbered between one and two million, and by the 1980s the birds had spread into previously unoccupied areas from northern Mexico to northwestern Canada.

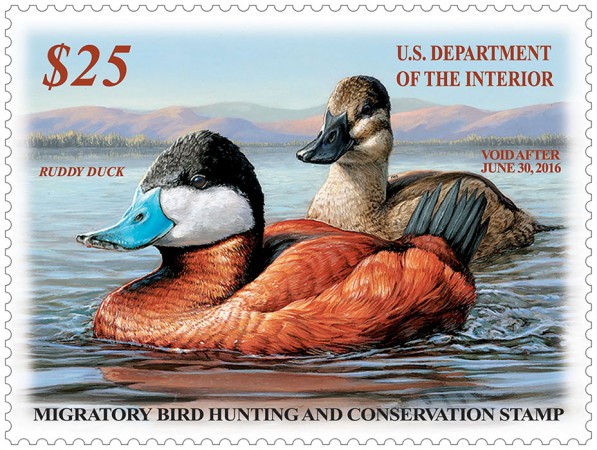

Originally, Duck Stamps sold for $1. Today you can buy a Duck Stamp for $25. Proceeds from the Duck Stamp are used primarily to secure habitat, with 98% of the revenue devoted to purchasing or leasing migratory bird habitat. In total, Duck Stamp sales have raised more than $850 million to conserve waterfowl habitat. Waterfowl hunting—one of the main causesof the Wood Duck’s near extinction at the turn of the century—is now generating funds to support waterfowl population recovery.

Harnessing the power of art for conservation

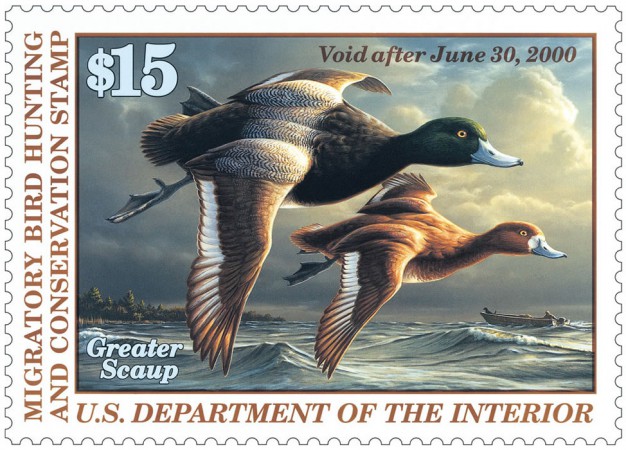

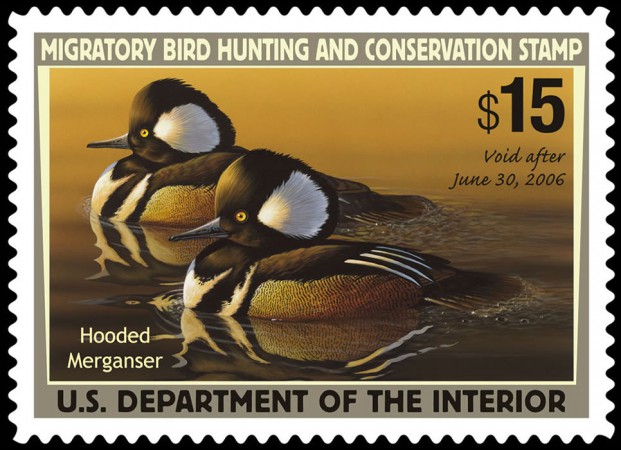

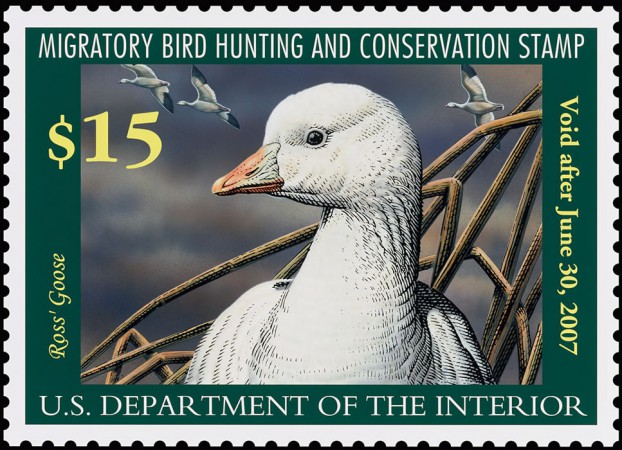

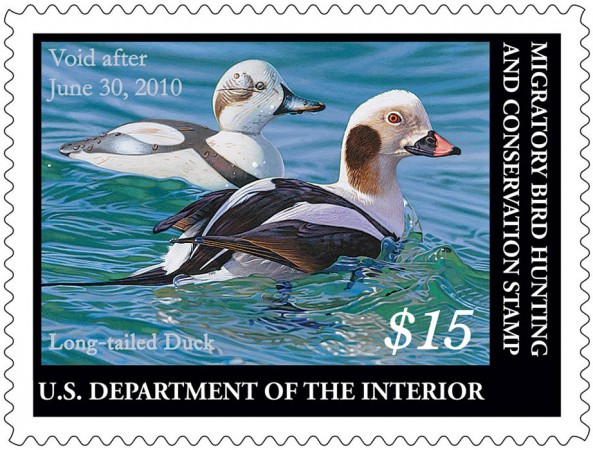

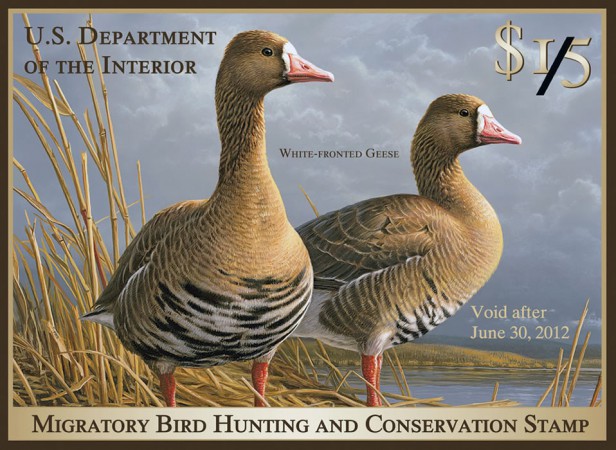

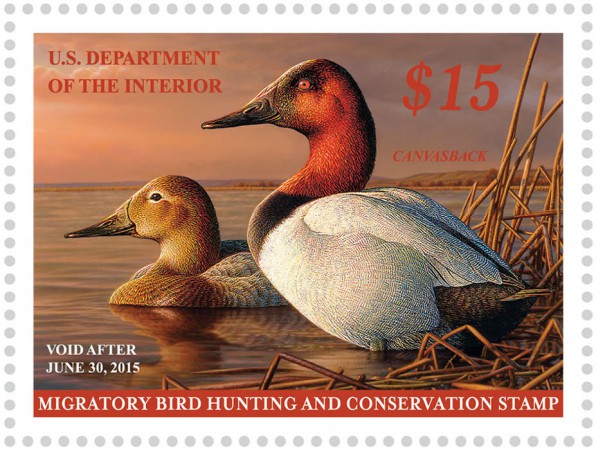

Ding Darling designed the first Duck Stamp. Accomplished artist that he was, he could have designed a full series. Instead, Ding encouraged wildlife artists nationwide to participate in painting Federal Duck Stamp designs. This brought fame and prestige to the program and allowed it to outlast Ding himself. The federal government held the first annual competition in 1949—essentially an early crowdsourcing campaign—with 65 artists submitting 88 Duck Stamp designs. This competition remains today as the only federally backed wildlife art contest, and the only art contest incorporated into U.S. legislation. Modern competition is fierce—with hundreds of entries annually—cultivating wildlife artists to get involved in conservation and prompting hunters and outdoor enthusiasts to support the arts.

In 1989, a Junior Duck Stamp competition was introduced, encouraging America’s youth to get involved from an early age. In just a few decades, proceeds from this program ($5 per Junior Duck Stamp) have supported school programs on waterfowl conservation and art education for hundreds of thousands of students.

As 14 year-old Sherry Xie put it in a 2015 conservation message contest, “Nature painted us the wetlands, but it is we who must conserve and appreciate the art.”

Why everyone should consider buying a Duck Stamp

The Federal Duck Stamp Program put the future of waterfowl in the hands of people who cared about waterfowl. At the time of its enactment, that meant the large number of Americans who were hunters, and it enabled a shift from unregulated waterfowl shooting to hunting that supported population recovery. Duck Stamp dollars are blind to personal perspective—98% of funds go to the perpetual conservation of critical habitat for migratory birds—regardless of whether a stamp was purchased by a skilled hunter or an inspired wildlife artist. Cumulatively, Duck Stamp funds have financed the purchase of around 6.5 million acres of waterfowl habitat—an area roughly the size of Maryland—across much of North America. This is a considerable amount of protected land, but further action is essential, as waterfowl habitat is continuously urbanized, converted into agricultural land, and destroyed to make way for new energy demands.

About 1.6 million people purchase a duck stamp annually, the majority of whom are active waterfowl hunters (1.1 million in 2014), a group in decline in the U.S. In fact, according to the 2011 United States Fish and Wildlife Service National Survey of Fishing, Hunting, and Wildlife-Associated Recreation, the people who identify as migratory bird hunters (~2.6 million) are outnumbered by bird watchers (~47 million), not to mention photographers, recreationists, artists, small business owners, and outdoor wildlife enthusiasts. These numbers illustrate the great potential to harness the direct conservation impact of Duck Stamp dollars. By the simple purchase of a Duck Stamp, millions of wildlife enthusiasts could stand with hunters to support a healthier future for the species that our national wildlife refuges harbor—which according to eBird, totals around 96% of all North American birds.

Although many duck populations have recovered, others remain threatened by habitat loss, invasive species, and changing water management. Today it is the waterfowl species of Southeastern marshes and ephemeral prairie wetlands—the Mottled Duck and Northern Pintail—facing population declines. While most other migratory waterfowl are doing relatively well at present, numerous other birds, including Baird’s Sparrow, Bobolink, and Marbled Godwit are supported by the same habitat used by waterfowl, and need our help more than ever.

From a human-centered perspective, buying a Duck Stamp has numerous benefits. A Duck Stamp permits admission to any U.S. fee-based National Wildlife Refuge during the year of purchase. Additionally, Duck Stamp dollars support healthy wetlands that: support diverse recreational activities, provide economic opportunities, purify our drinking water, promote wildlife observation, photography, and art, and shelter coastal communities from storm surges.

By combining the needs and desires of humankind with those of wetland ecosystems, the Federal Duck Stamp Program preserves the functioning whole—a whole made up of ducks, nongame birds, hawks, owls, mammals, fish, and wetland and upland plant species. We can admire the incredible beauty of the Wood Duck—as well as the additional 40 species of migratory waterfowl in North America—knowing that our support of successful conservation programs like the Duck Stamp will ensure that future generations will find equal or greater sources of wonder.

Keeping ducks common

Tara Tanaka is a professional photographer with a passion for ducks. She lives in Florida with her husband Jim Stevenson, a wildlife biologist, where the couple delight in observing local Wood Ducks, Wood Storks, Black-bellied Whistling-Ducks, and Hooded Mergansers in a cypress swamp near their house. After learning how important the habitat is for such species, the couple felt compelled to purchase 45 acres of the cypress swamp in 2007, which they now manage as a wildlife sanctuary.

During the breeding season, Tara is “on call” from dawn to dusk in her effort to film fledging Wood Ducks: “I went out early to try to be less of a disturbance, cleared the mosquitos out of my blind with the bug zapper, and got two cameras w/tripods in there. I looked up and she was sitting in the entrance, looking pretty calm. I knelt down and shot some video, then slipped out of the blind to get the other scope, I guess somehow she had never seen me until then, and suddenly she jumped out of the box and flew about 75 feet across the grass. I got everything set up and waited— it was an hour before she returned. Finally I saw another little face in the opening and knew it was the day.”

After spending well over 1,000 hours in her blind, Tara has noticed that individual Wood Ducks—particularly hens—have distinct personalities. “Some females spend more time preening and less time watching, meaning their young go unprotected…every predator including alligators, crows, and Red-shouldered Hawks, know when the baby ducks are hatching.” But it’s not just predators that Wood Duck hens have to guard against. In cavity-nesting ducks such as Wood Ducks, females often try to lay an egg in another hen’s nest to escape the responsibility of incubating and rearing their own young, a behavior termed “egg dumping.” Some Wood Duck hens are more vigilant than others, and Tara has seen “triumphant hens” that “took out the dumped egg, first punctured it, then sank it, and then proudly flapped her wings.”

Neither Tara nor Jim hunt, but both enthusiastically buy duck stamps annually to support conservation and to gain access to fee-based National Wildlife Refuges. They are in the process of obtaining a conservation easement to protect their swamp sanctuary for posterity. The experience of living among Wood Ducks and “getting a daily dose of the life cycle of diverse species,” Tara said, “has brought us more joy and satisfaction than words can express.”

Catch some of Tara’s stunning captures at the start of this story.

You can support local wetlands and wildlife by donating your effort, materials, or money:

- Buy a Federal Duck Stamp/Junior Duck Stamp to support conservation

- Visit a wetland or national wildlife refuge

- Conserve wetlands on your property—encourage your neighbors to do the same

- Consider conservation easements

- Support organizations like Ducks Unlimited and Friends of the Migratory Bird/Duck Stamp

- Educate yourself and others on waterfowl and wildlife in your area

- Take a waterfowl identification course through the Cornell Lab

- Download and use the Junior Duck Stamp curriculum

HELP SAVE AMERICA’S WATERFOWL

Helping to preserve wetlands and save America’s waterfowl is as easy as purchasing a Duck Stamp. Whether you’re a hunter or an outdoor recreationist, you can make a difference right now by by purchasing a Duck Stamp/Junior Duck Stamp from the United States Postal Service.

About The Author

Dr. Alexandra Class Freeman has studied the lives of wild birds on four continents. She draws on her experiences to share conservation stories with people, describing how the lives of birds and humans intersect as postdoctoral researcher at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Alexa’s favorite North American duck species is the Harlequin Duck, a sea duck with speedy agility, incredible glamour, and call sounding like the squeak of a mouse. Alexa’s aim is to encourage people to reflect on their relationship with nature and to take an active role in conserving the biodiversity that provides inspiration to us all.