How to Paint Birds with Jane Kim

[Audience talking]

[Kevin] Hi, welcome to the special seminar, special talk by Jane Kim about her Wall of Birds. I’m very excited about being here and I hope you all are too. I’m Kevin McGowan, I’m with the education section of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and I have been here a long time and I’ve seen some good things come through, and Jane is one of the best, so it’s, it’s really a pleasure.

[Laughter]

[Kevin laughs]

So I met Jane back in 2010 when she came in as a Bartels, what we called interns then, now illustrators, uh and it was really fun to, to uh see what she did. I work with the illustrators fairly frequently. I can’t draw a stick figure,

[Laughter]

but I know what birds look like

[Laughter]

and I’ve developed the ability to be able to tell people what’s wrong and to polish already good work. So I have been working with the illustrators, I’m still working with the illustrators, and it has always been a great privilege to be able to watch what they do. And so when Jane came here I worked with her a little bit, and I was showing her a few things. And I’m pretty sure I slightly improved a couple of things in the beginning. But then I sort of turned to her and said, why are you here?

[Laughter]

Why aren’t you out making big bucks? And she said, no, I’m learning a lot. I’m learning a lot. And I think she did. And I think she had a good time here. It was certainly great fun having her here. She’s a very positive person, very fun to talk to and see what she’s working on.

Um I was struggling with some things with I was creating a couple of online courses, and I was left to do some of the graphic design by myself, which was a horrible mistake.

[Laughter]

And so I remember putting things out to Jane, and showing her a few things, and she was always so encouraging about things. I had one thing that I was, struggled to get a concept across. And she’s like, oh, that’s so good, that looks so great. And I said, well, you could make it look better, right? And she said oh, yeah, yeah.

[Laughter]

So when the announcement was made to create the Wall of Birds, I was thrilled that it was going to happen for a couple of reasons. One, that I was absolutely thrilled to the thought of having Jane back here to interact with again. And, Fitz had always been since the building had been built, John Fitzpatrick, our director, he always would look at the walls and sort of mutter to himself, well, we gotta, don’t you think we need to have something up on the walls?

[Laughter]

And we’re like yeah, we need something up on the walls, ugh. And you could just see him every now and then, he would be coming up and down the stairs and he’d just look at these blank walls and say something needed to be done.

[Laughter]

And it, it’s just such a wonderful way that it all came together. Every day that Jane was here working on the wall, she did a lot of stuff at night. And so I’d come in the morning, and you never knew what would be up there next. And it was always exciting to uh, to see what had been put up on the wall the night before.

And uh it was also fun to take a break. You’re sitting at your computer, and you’re working hard, and it’s like ah, I’ve got to get up and do something. Maybe I’ll go down and see what’s, what Jane is doing on the wall.

And you would see her up there on the lift, painting away, and it was, it was really a spectacular project to watch. And, you know I wasn’t involved that much in it. But enough to feel that it was, it was really a special, special thing. I think one of the things, most amazing things about Jane’s work is that she works at such scales. So from tiny, small, detailed things, to these giant masterpieces. I mean, she paints on barns, and buildings, and things like that.

And then if you look at the detail, if you just look at like, one of the largest birds on the wall out there is the, the cassowary, the life-sized cassowary. And you look at it and there are thousands and thousands of tiny little marks on there, the brush strokes that are just incredible to see how it goes from that, that small to the big.

I want to thank Jane for one other minor thing. When she finished the wall she and her husband Thayer hosted a karaoke going away party.

[Laughter]

At the K house. And I have to say, karaoke was always a, a, uh pathological fear of mine.

[Laughter]

And uh, for Jane, I went, and participated in karaoke for the first time ever.

[Jane] Yes!

[Laughter]

[Kevin] Which was interesting.

[Laughter]

And, I was certainly not surprised, a little angry, perhaps, but that Jane is a spectacularly talented singer and karaoke woman. It’s like, ugh, so much talent all in this one little person.

[Laughter]

You know, it’s just those of us who don’t have that kind of talent start to get a little jealous every now and then. But it’s really so special to see such great artistic talent, um intelligence, wit, beauty, great singing voice, and such a joyful personality. She’s been a pleasure to be around. And I feel I am very fortunate to be able to work with you, and to know you as a friend.

So would you please all join me in welcoming Jane Kim tonight.

[Applause]

[Jane and Kevin hug]

[Jane] Hi, you can all hear me? I’m going adjust this here. Oh, thank you. It is so wonderful to be back here. It has been, uh, four years since the project was complete, um completed. And I haven’t been back since, so I really can’t think of a better reason to come back than to have had some space from the mural, quite frankly.

[Laughter]

Um, some time to reflect, and to share uh this book that that Thayer Walker, my husband and business partner, and I wrote together chronicling um just some of the stories that I could remember from the project, after having some time.

Um I would really like to thank the Lab once again. Uh, you know, Ink Dwell which is the name of my art studio, was only created maybe a year or two after I left being a Bartels intern.

[Slide text: Ink Dwell

Art, Wonder, and the Natural World; Images: Scientific illustrations of various animals including a crow, toad, fox, moth and more, a fungus, and a plant. An illustration of an egg is between the words Ink and Dwell]

And this project here with the Wall of Birds was sort of the beginning of that career. And so I am forever grateful to, to Fitz, to Dr. John Fitzpatrick, for believing in me. Um, it was remarkable what, uh, the opportunity, and the opportunity that the Lab really gave to me and my career, and helping me shape uh what kind of artist that I want to be.

So tonight is going to be a lot of reading from, from the book, and also sharing a little bit of history of, of my work. So without further ado, what I would really love to share and open with is John’s foreword. It is quite moving, I’m not going be reading the entire um, excerpt. But just some, some moments of that.

So, foreword. The early 20th century was an artistic heyday for natural history museums as they invented new ways to bring spectacular natural places, exotic species, and conservation ethics to their visitors. The hallmarks of that era were dioramas, three-dimensional masterpieces of taxidermy and background painting created by superb taxidermists and master artist naturalists.

These craftsmen, and they were indeed all men, knew their subjects intimately, often traveling the world to document real places with field sketches before melding knowledge and passion into timeless replicas of biological diversity. The background painters included such legendary wildlife artists as Louis, Louis Agassiz Fuertes, Carl Run, Run, sorry, Rungius, and Francis Lee Jaques, while artists like Charles R. Knight and Rudolph Zallinger became equally legendary for painting monumental murals depicting prehistoric life.

I just really connected with that very first paragraph because indeed, when I left the Rhode Island School of Design,

[Photos: Two views of exhibits of bird skeletons at the Page Museum, with a painting of what the bird would look like on the wall behind each skeleton]

I moved immediately to San Francisco, and, you know, it took about six years before I decided to apply to the science illustration program at the California State University in Monterey Bay. I had always had a great affinity towards technical drawing and the natural world, but there were precise moments, um, in that time between 2003 and 2009 that left uh lasting impressions.

And this particular piece, um, does anyone recall where this is? This is at the La Brea Tar Pits at the Page Museum. And in the middle of their exhibit are these phenomenal cases, these glass cases of articulated bird skeletons. And that’s of course interesting in and of itself. But behind that, were these remarkable paintings by John Dawson.

You might also recognize his work through the collection of postage stamps that he created, those habitats postage stamps. But I was absolutely mesmerized and enamored by the work and the, the value that these paintings added to my understanding of these birds, and the experience in the museum.

So there was a real aha moment there where I thought to myself, this is what I want to do. So I really started to pay attention to moments like that. And decided to pursue a career in scientific illustration. So now I, I really sort of work in tandem with visual art and the discipline of science illustration.

And I had the great fortune

[Image: Painting of three Hawaiian honeycreepers in a tree with a yellow flower]

of working with um Fitz directly on the project when I was here as a Bartels intern. and this is one of the pieces that I worked on with him. You know, it’s funny, it didn’t actually end up being used for anything, but man, was it great fun to make [laughs].

[Laughter]

And so, uh I’m gonna just continue reading a little bit more from his passages. The Cornell Lab has embraced the intimate relationship between art and ornithology throughout its 100 year history. The Lab’s founder Arthur A. Allen was a close friend of Louis Agassiz Fuertes and a mentor of the noted artist and ornithologist George Miksch Sutton at Cornell. Allen pioneered the art of color photography in nature and he launched the Lab’s first journal, The Living Bird, which featured paintings and sketches deftly intermingled amid its scientific articles.

The new building provided space to begin hosting artists in residence, and soon our longtime friends Phil and Susan Bartels began funding the Bartels science illustration program. Consequently, from 2007 to the present, the Lab has hosted a Bartels illustrator on staff almost continuously, each one selected from a highly competitive pool of early career illustrators and graphic artists.

Jane Kim came to the Lab as a Bartels illustrator early in 2011, a talented young artist with a bachelor’s degree from Rhode Isl— blah, blah, blah, yeah that part you’ve, you got.

[Laughter]

Um, so the aha moment came when word filtered around the Lab that Jane had won a design contest for a series of outdoor murals which she proposed to paint in central California.

You’ll see those murals um, later in the slides.

Mural, I thought, we have an in-house artist who is interested in murals? I rushed to find Jane, and after congratulating her, I asked her to accompany me out to our second floor walkway,

[Laughter]

where I pointed,

[Laughter]

[Photo: Large, empty green wall where the mural would be painted]

at the enormous empty olive drab wall. I don’t know if you can tell in this picture, but you can see it in the corner there, it was a completely different color. Um it was sort of this olive drab green color. There was nothing on it. And, and uh, where was I? So on this olive drab wall, my dream of a grand mural depicting aviation evolution had scarcely left my lips before Jane’s eyes opened wide and she shouted “I want to do it, please, let me do it!”

[Laughter]

I asked her to develop a design and the project was born.

So this is really where I need to be so grateful that uh he believed in that. He had asked several other artists before me. And this is also in his foreword, that had said, oh, nice idea, but uh it’s just way too big of a project, I’m not gonna take that on.

So I was fresh enough and young enough,

[Laughter]

and wide-eyed enough to tackle that really with everything that I had. And I would do it again in a heartbeat [laughs].

So I’m going to kind of backtrack a bit, and give a little bit more information about the work that we do at Ink Dwell studio because it is really sort of an umbrella studio of a bunch of different things we do science, straight science illustration.

[Image: Ecological map of San Francisco with scientific illustrations of plants and animals throughout]

This is an ecological map of San Francisco that was fully illustrated that just was released last year. The front and the back.

[Image: Back of the ecological map of San Francisco with four different smaller maps, a painting associated with each, and additional information and illustrations]

You know, illustrations for magazines,

[Image: Magazine page showing illustrations of red-tailed hawk in flight, bobcat with rodent in its mouth, a spider, a fungus, and more with text below]

I’m sure you’re familiar with uh, you know, Living Bird, and how important illustrations are to that. Well this is for a magazine called Bay Nature in California. Done

[Photo: Diorama of fish at the National Aquarium]

my own version of diorama and backdrops for institutions like the National Aquarium.

[Photo: View of the touch tank at the National Aquarium with guests reaching into the tank with the help of an employee, and the diorama visible in the background]

Um also practice

[Photos: Interactive visual art exhibits of person standing behind a plant with only his legs visible, and a display on the wall with headphones attached]

fine art. Um this is from a show that I curated in, in Oakland um around sense, sensory experience and botanicals.

[Photo: Gallery at de Young Museum with a large open space, art on the walls, and several clear partitions with some stands and a table visible]

Um this is the de Young Museum in California.

[Photo: Alternative view of the gallery, showing the display on one of the stands]

So you know really where, there’s such a breadth of, of ways to visualize and communicate nature and science. We even do decorative art.

[Photos: Paintings of Douglas fir pine cone, pair of black-billed magpies and their nest, and microscopic view of lichen in private home]

So [laughs], these are just some pieces from a private home. Um that I just completed. And really this is my favorite. This is actually a microscopic view of lichen in a bathroom.

[Audience exclaims and laughs]

[Audience] Awesome.

[Jane] It is an appropriate place for it [laughs]. But public art really has been

[Images: Two circles, both with “Migrating Mural” written in them, one with a bighorn sheep painting and one with a monarch butterfly painting]

the great passions for Ink Dwell. And the mural series that Fitz refers to in his foreword is for a project called the Migrating Mural, which is an ongoing Ink Dwell series. And the Migrating Mural is a series of art installations painted along migration corridors of wildlife that they share with people. So our very first series was highlighting the Sierra Nevada bighorn sheep in California along Highway 395.

[Photo: Male bighorn sheep mural painted on the side of one of the buildings at the Mt. Williamson Motel, with a mountain range visible in the background]

[Audience exclaims]

And it covered about 120-mile stretch from Lee Vining to Lone Pine. So these are just a couple of closeups from the series.

[Photo: Mural of bighorn sheep running from mountain lion]

And here is a map

[Slide text: “Conservation work is often done far from the public eye. The Migrating Mural is a unique and beautiful way to communicate our need to protect endangered wildlife and the ecosystems upon which they rely.”

-Dr. Tom Stephenson, California Department of Fish and Wildlife Sierra Bighorn Recovery Program; Image: Map showing locations of murals along Highway 395 in California, and photos of six bighorn sheep murals]

that just showcases um the locations of the works. Um and one of the things about what we do, we, we truly believe in being able to use art as a vehicle. Um not just to visually excite, but also to help tell narratives and stories and conservation stories. So we partnered with the Department of Fish and Wildlife, California Department of Fish and Wildlife bighorn sheep recovery program, as well as the Sier, Sierra Nevada bighorn sheep foundation. That’s a mouthful [laughs].

And so we created six unique pieces highlighting different aspects of the herd’s um biology. And our focus currently

[Slide text: Through public art installations across North America, the Migrating Mural will trace the path of the monarch butterfly, which migrates from Mexico to Canada. It will bring to attention the immediate need for habitat conservation and restoration; Image: Monarch Migration Map showing Overwintering Roosts, Fall Migration Route, Unconfirmed Migration Route, Resident Population, and Migrating Mural Sites]

is around the monarch butterfly. So you can see that the migration, there is two populations. The western and the eastern. But, almost the entire lower 48 is connected by this one special insect. So it was a really wonderful sort of second iteration of our project to really connect the entire country.

And uh we began the project in the fall of 2017, and we have seven installations to date.

[Photo: Kaleidoscope mural of monarch butterflies on the side of an airport control tower in Springdale, Arkansas]

So our first one, this piece is called Kaleidoscope. It’s in Springdale, Arkansas. It’s on an airport control tower. Perfect location for our first mural.

[Photo: Mural of monarch butterflies on the side of a white building]

Um this is in Winter Park, Florida at Full Sail University. And this was a really beautiful partnership between two other organizations, Full Sail University and The Nature Conservancy in Florida.

Um so we were able to tell their story, and they created a brand new initiative called the Monarch Initiative, which is really, was really fun to be a part of that.

[Photo: Two people painting the mural, with one standing on a ladder and the other next to a ladder]

And I’m also going to share a time lapse video of the process because it is really fun to see everything sped up [laughs].

[Screen view changes out of presentation to Monarch Migrating Mural Time Lapse video]

[Video: Time lapse of Milkweed Galaxy being painted in Winter Park, FL. The building starts off all white. People come in with ladders and a lift. They draw the design on.; Audio: Music playing]

So our murals, unlike the one here in the Lab, these outdoor projects usually take anywhere from four to six weeks.

[Video continued: They start painting the mural]

We always have a team as we did here with the Lab to create these, these works. And it’s funny, it kind of becomes like a big paint by number.

[Laughter]

Really, when it comes down to it it.

[Video continued: They attach stencils of a monarch to the wall, then they are removed.]

Here we’re putting up the stencils that we trace the image, and then fill it in with the colors.

[Video continued: More sections are painted.]

And it was really one of the weirdest winters in Florida. Normally, February is a beautiful month to be outdoors.

[Video continued: The finished mural; Text: © Ink Dwell LLC, 2018

Milkweed Galaxy by Jane Kim]

But it happened to be just this insanely humid and cold winter, and there were days when it was about 90-something percent humidity, and the paint would just melt. Just completely melt off the wall. I mean, I was actually in tears.

[Video continued: Text: The Monarch Initiative Protecting Pollinators, The Nature Conservancy Full Sail University Ink Dwell; Audio: Music ends]

This mural never brought me to tears, that one actually did [laughs].

[Laughter]

I had to shed a couple of tears for that. So that is just a little snippet of that, that process.

Uh, let’s see. We are… there, yeah? Okay,

[Photos: Monarch butterfly and caterpillar in front of the mural]

and one of the other things that we really try to do anyway is, is activism and um encouraging our partners to also do some on the ground conservation work. So Full Sail actually re-landscaped the facade and planted milkweed to provide butterfly habitat for uh that campus.

[Photo: Person on a lift painting Midnight Dream mural of monarchs on a blue background]

And here is, this is called uh Midnight Dream in downtown Orlando. And I’m just showing this for scale, as Kevin talked about scale. Quite a different scale.

[Photo: View of the entire Midnight Dream mural on the side of a building]

We love working with students.

[Photo: Child with black and white drawing of flowers and caterpillar]

Education is such a huge part of what we do as well. And this is with a group of 15 kids at SF Day

[Photo: Group of kids outside in front of a small mural of caterpillar and flowers drawings]

and they created this mural with me and my team.

[Photo: Banners showing the lifecycle of the monarch butterfly]

These are series of banners that are now hanging, uh flanking the entrance of

[Photo: Ogden Nature Center entrance with banners visible along the road]

the Ogden Nature Center in Ogden, Utah. And these were just recently completed this past October.

[Photo: Jane painting a mural of a monarch]

[Photo: Full view of the mural with a house visible in the background]

This is called Monarch in Moda, and it’s a big parking lot structure to a building called the Monarch,

[Photo: Another view of the mural around the parking lot]

which is an art studio and a creative space and gallery. And coffee shop. Everything. And this is at Weaver State University.

[Photo: Mural with various stages of monarch lifecycle on an interior wall near large windows]

This is an interior mural.

[Photo: Another wall of the same mural]

[Slide text: MURALS, FIGURATIVE ART, and NATURLISM, SCIENCE ILLUSTRATION]

So, murals, figurated—figurative art, naturalism, science illustration, these are all the categories that uh really embody Ink Dwell, and honestly, I could probably give an hour talk just about each one of these disciplines. They are so complex. But I just wanted to quickly

[Photo: Altamira cave painting of several bison]

talk about what they mean to us. You know, public art and painting on the walls, and depicting the observed world around us is, is really just a human function. Uh it’s been for thousands and thousands of years this tradition has um been an expression, you know, fundamental to the human condition. Um and so I think about this a lot as, when I think about art as a vehicle and a voice and a common language that we can all relate to. So that’s quite important to me.

[Photo: Inside the Sistine Chapel]

Telling stories, you know, this is the Sistine Chapel and I really believe that monuments and, and this particular platform has an important part to understanding the, the nar—the culture around us, and our current ecosystems. And there aren’t nearly enough uh monuments to nature.

And so I really appreciate Todd McGrain’s project, that passenger pigeon, that statue that you see as you walk in, The Lost Bird Project. Maya Lin’s work.

[Photo: Part of Pan American Unity mural by Diego Rivera]

Um you know we have so many other types of murals that touch on, on um culture, so, you know in Diego Rivera’s words, my mural will picture the fusion between the great past of the Latin American lands as it is deeply rooted in the soil and the high mechanical developments of the United States.

Um so I’m really proud to be able to have this mural stand for the evolution and diversity of birds. And really monumentalize that for the world.

[Images: Four medieval paintings of animals]

And of course naturalism, and science illustration, I really appreciate sort of the historical trajectory that that has gone through. You know, in the medieval era, bestiaries were very common. These encyclopedias of animals and the depictions of them were actually so much more symbolic. And so I’m quite attracted to [laughs] these depictions of animals that are meant to not capture the actual details and the observed details, but meant to capture a spirit. And I just wanted to sort of throw in a very early painting of mine

[Image: Painting of large flower and small cat]

from, gosh, this is probably from 2007, where, um, you know it had been before I was very attracted to the idea of conveying information. Um and these were just a bit more of my musings. But nonetheless, I really appreciate what science illustration has given the world,

[Images: Duck drawing by Leonardo da Vinci and Stag Beetle by Albrecht Dürer]

and so thinking about really the, the foundation of that was the Renaissance. And the growth of knowledge in medicine, in human anatomy, in just understanding the world around us. The printing era, you know the dissemination of information. It was just so profound.

So this is a picture of a duck by Leonardo da Vinci, and of course Albrecht Dürer and on the right, just masters. And of course the role that scientific illustration

[Images: Four scientific illustrations of penguins from Antarctica by Edward Adrian Wilson, some with handwritten notes and some with backgrounds included]

has played for the world. Um these are some of the earliest depictions of um, Antarctica on the 1902 um Discovery expedition. So these are by Edward Adrian Wilson. You know this is before photography. Can you imagine coming back and saying, there are these weird birds that are about this high, and they don’t walk very well. How do you really describe that? Um so I really value you know philosophically what science illustration has given us. So that leads us to

[Photo: Jane on a scissor lift painting part of the way up the wall partially through the mural]

this project, and uh where Ink Dwell is today. And so one of the things that I think the book does um, is that it allowed me to take a moment and reflect on the project. And uh, you know, one of the questions that I get asked often, if I’m talking about my work or presenting my work, is, oh, well, do you ever do humans? And my answer, actually, is honestly, yes, I’m doing humans all the time, but metaphorically through the natural world.

And so there are so many stories that we can learn about ourselves, by observing, by observing nature. And so this book was an opportunity to share some of those stories that I learned myself uh from, from the wall. So I’m just gonna read a little excerpt from my intro.

Um, so Thayer Walker is, as I mentioned is my husband and business partner, but he’s also a writer and journalist. And he and I worked on this book together, so the words that he—that are in this book are written by him who is a much better writer. so I’m actually eternally grateful that tonight I have these beautiful words to read to you [laughs].

Um so I’m gonna go ahead and, so creating this book has been cathartic. It is the first time that I felt the freedom to reflect on the project as more than just an unbelievable amount of hard work. In doing so it occurred to me that birds were the perfect subjects, both aesthetically and metaphorically, for a mural exploring diversity and evolution.

These days in America, at least those topics diversity and science, have become alarmingly divisive. Birds provide a comfortable entry point, who doesn’t love birds? They come in a rainbow of colors and a variety of sizes. They have distinct personalities and display behavior that we can recognize as our own. They are our neighbors and often our closest connection to the wild.

Many readers holding this book could walk out their front doors or look out their windows even and have an experience with a bird. We created this book with the intent to do more than simply highlight beautiful photographs of art on a wall. We hope that in addition to providing a window into my personal journey, it will showcase a broader cultural and geographic transcendence of birds, and their ability to teach us about the human condition. From romance and the creative process to equal rights and immigration, and in devoting the last several years of my life to birds, I learned as much about myself, as I did about them. And for this, I am eternally grateful.

So we have copies of that here [laughs].

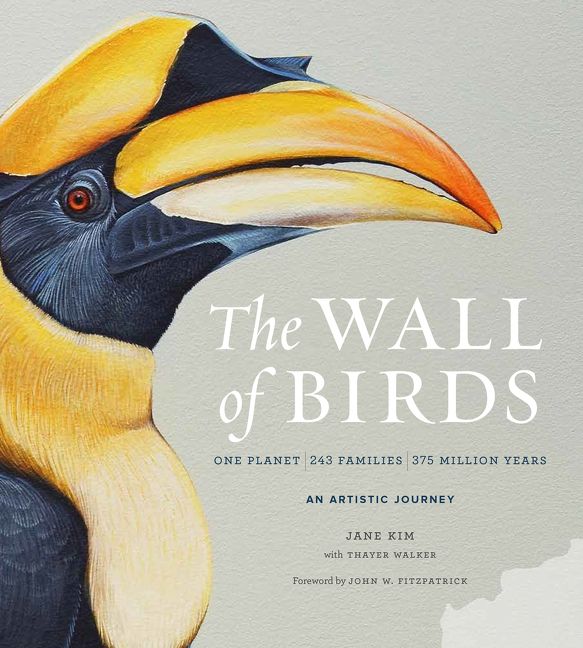

[Image: The Wall of Birds: One Planet, 243 Families, 375 Years

An Artistic Journey book, with the great hornbill painting on the cover]

That was a little weird and out of order, wasn’t it?

[Photo: The wall before the mural was started, with Jane walking in front of it]

So here is the wall uh as I remember it in August of 2014. And I’m gonna read you a passage called The Blank Canvas.

[Image: Page of the book with “The Blank Canvas” heading with a photo of Jane in front of a blank space on the adjacent page]

The canvas, wrote Vincent van Gogh, has an idiotic stare and mesmerizes some painters so much that they turn into idiots themselves.

[Laughter]

Many painters are afraid in front of the blank canvas, but the blank canvas is afraid of the real, passionate painter who dares and has broken the spell of you can’t once and for all. We artists have a famously conflicted relationship with the blank canvas.

Cezanne once lamented it as so fine and so terrible. And the playwright Stephen Sondheim described the dilemma it presents as the need to bring order to the whole. The blank canvas is a world of possibility and inner ring of hell. The aesthetics of negative space represent limit, limitless potential. It can be the beginning and the end, quiet and loud, everything and nothing at all. And the terrifying part, the compelling, the feeling that I’ll never shake is that my work won’t make the blank canvas more beautiful or compelling than it already is.

As I imagine them my paintings are a triumph. The challenges and insecurities result from trying to make the finished work match the concept. And the scale and setting of the Wall of Birds only amplified those feelings.

So it was, it was quite terrifying. I don’t know if many of you recall what the, the wall—at least the hallway and the stairwell looked like before 2014. But, works of all the great masters were hanging on this wall.

Um, and, and, I remember when I first designed my very first concepts, I left space for them, because I just couldn’t even imagine that they would take those down, and I remember having a conversation with Fitz you know saying you know, I’m feeling like there is just not really enough room to showcase all of these families of birds. There’s a lot of real estate to cover. And he’s like, well why don’t we just take those paintings down. And I sort of froze. Like, really? That is what is going to happen?

And that pressure to sort of fill that wall with even, or work that could even match up to that was, was quite, quite terrifying. But I did, you know, the most reasonable thing, which is well, let’s just fill it with something—no, that really wasn’t it.

[Photo: The wall after only the world map had been painted]

But, the world map, um

[Laughter]

was the sort of connective tissue of the mural. We went through many iterations of how to depict the bird families, and I always came back to this because you know the first thing that people do when they look at a map, is to try to identify where they are, or, where they have been, or where they hope to go.

And so in that way, um putting the birds of the worlds on there really amplified that, that feeling of connection. So it was, just made the most sense to me. Um the map is not super accurate, so I hope that that—you will forgive me on that. But a lot of the continents had to sort of be shifted around in order to

[Laughter]

[Photo: Partially completed mural with cassowary, ostrich, and some other birds painted, additional stencils being positioned, and the lift in front of the wall]

to make it correct. Um, you know, and so this is just a few months in. And it still looked so sparse. Um and I remember thinking, oh, my gosh, am I —I’m going to pull this off, right? These are the conversations that I was sort of having daily with myself. Um so, one of the things that I learned very quickly was, you gotta create almost an assembly line sort of systematic way of, of, of working.

[Image: Concept sketch depicting evolution of birds to the left, then a world map with birds distributed throughout]

And so actually before I even came to the Lab, the, the concept was almost, well, no, it was completely created. It didn’t deviate very far from this original design. You know, the other thing we did was create

[Photo: Several final drawings of birds and a hornbill skull on a table]

these very specific final drawings, and I’m so grateful to Jessie Barry too, for being my scientific adviser, and along with many other staff here at the Lab who, including Kevin, who looked at my renderings to make sure that I was accurately portraying all of the animals.

And then, you know, all of that work had to be figured out

[Image: Drawing of male northern cardinal]

[Image: Final painting of northern cardinal]

beforehand.

[Image: Drawing of wood duck]

[Image: Final painting of wood duck]

So that when it was time to paint them on the wall,

[Image: Drawing of yellow-billed magpie]

[Image: Final painting of yellow-billed magpie]

it was just production.

[Images: Loop of previous drawings and paintings of the three birds]

I didn’t have to make choices about the anatomy or how I was going to position them. The other thing that ended up happening was creating this

[Image: Pages from the book showing color chart]

beautiful uh Pantone, avian Pantone chart. Um so, you know, seventeen months is a really long time to try to make a consistent work of art. So having a palette that I could rely on, that continuity of colors, and um highlights and shadows, and all of these things were all done with this palette. And so the birds

[Image: Pages from the book showing the subdesert mesite with base colors blocked in and the finished painting beside it, with color charts next to each]

were first blocked in with that, the palettes represented by the circles. Um and then details were then painted with acrylic paint. And then we discovered a really

[Image: Pages from the book showing six birds from East Africa: Hartlaub’s turaco, western nicator, African paradise-flycatcher, superb starling, lilac-breasted roller, and red-and-yellow barbet with text on the opposite page]

interesting moment. Like I said, there were so, as many discoveries in writing this book as in painting the mural itself. And so this moment right here, actually, was one that Kevin pointed out to Thayer and I, which actually speaks to all of the different ways that birds get their color. So I’m gonna read that to you.

Africa’s Lake Victoria grouping represents many of the color types that characterize birds. Melanin, the same pigment that gives humans our own coloring produces blacks, grays, and earth tones like rust and gold in feathers . The burnt sienna of the African paradise-flycatcher’s tail and the black on its head is the result of melanin.

In addition to adding coloration, melanin also strengthens feathers, which is why white birds like the wandering albatross have black wings and wing tips, the places where air currents cause the greatest wear and tear.

The iridescence on the neck and back of the superb starling comes not from pigment, but from structural color. The starling’s outer feathers are constructed in a way that refracts light like myriad prisms, making the bird appear to shimmer.

The eponymous coloring of the lilac-breasted roller results from a different kind of structural color, created when woven microstructures in the feathers called barbs and barbules reflect only the shorter wavelengths of light like blue and violet.

The primary colors that lend their name to the red-and-yellow barbet are derived from a class of pigments called carotenoids that the bird absorbs in its diet. These are the same compounds that turns flamingoes’ feathers pink.

As a member of the family Musoph—Musophagidae—did I say that correctly? Yes. The Hartlaub’s turaco displays pigmentation unique in the bird world. Birds have no green pigmentation in most cases, and verdant plumage is a combination of yellow carotenoids and the blue structural color. Turacos are an exception, displaying a green copper-based pigment called turacoverdin that they absorb in their herbivorous diet. The flash of red on the Hartlaub’s underwings comes from turacin, another copper-based pigment unique to the family.

So in this one moment, it happened to actually be a beautiful lesson about, about bird color. And, coloring

[Image: Pages from the book showing long-tailed jaeger, beach thick-knee, and green broadbill with text]

structural color with pigment is quite a challenge. Um and I am going to share a little story about this um green broadbill. The green broadbill—oh, I guess I’ll move up. In Southeast Asia, the beach thick-knee and the green broadbill make for a dynamic if unusual pairing. Exquisitely patterned, yet dull in color the wide-ranging thick-knee is one of the largest shorebirds. I planted it on Sumatra, a grand exclamation point atop Indonesia’s largest island.

The thick-knee takes a commanding posture, casting a long gaze across the Malay Peninsula, where it adds compositional depth. The green broadbill is a different character entirely, a small, retiring rainforest passerine. Given its size, it really should have only taken a few hours to paint, but I spent nearly that long mixing a dozen different shades of green, in an ultimately fruitless effort to capture its iridescent emerald coloring.

[Photo: Green broadbill; Image: Green broadbill painting]

And ultimately I had to go buy a tube of fluorescent paint,

[Laughter]

which still couldn’t quite match the bird’s hue. So as usual, nature wins. And I remember that moment of man, I cannot capture this green. It’s driving me nuts! So after writing this passage with Thayer, you know, I started reflecting on another

[Photos: Breeding male indigo bunting in shadow and in sun]

idea for a painting. I was invited to be an artist in residence at the Woodson Art Museum, the Leigh Yawkey Woodson Art Museum. Um I’m not sure if many of you know about the birds in, annual birds in art exhibit. Um but they have a 40-year annual exhibit um just highlighting people who depict birds in their artwork. And so I decided to create a story about blue pigment.

I don’t know if any of you noticed in that passage, um but, blue is not a pigment that exists in birds, and so that dilemma of how do I accurately depict a blue colored bird? It’s, it’s really hard. So I created this painting called

[Slide text: RGB(ird)]

RGBird.

[Laughter]

And, this is the piece.

[Image: RGB(ird) painting with many male indigo buntings flying through and around a color wheel]

And I highlighted the indigo bunting, so that picture I showed a couple of slides back it’s just that difference, you know, of when the light is hitting it just right versus, when it, when it’s in shadow. Totally different perception. And so that was an interesting concept for me to play around with was, was perception.

Um and so, the, the bird, the indigo buntings are flying through a color wheel and of course, red, green, blue, is the color model that our eyes see and observe light—uh color through light. And, pigment is a complete opposite medium. You know when you mix all colors of light together, you get white. You mix all pigments together, you get black.

So you know it really was this push and pull. So the shadows that these birds are casting are not meant to be literal shadows, but representative of different levels of light. And how the same four birds in different levels of light, might appear completely different.

Okay, so,

[Image: Pages of the book with heading “Compromise and Composition” with paintings of black-necked crane and Przevalski’s rosefinch; Dartford warbler, great spotted cuckoo, and white-throated dipper; painted sandgrouse, red-whiskered bulbul, and white-throated kingfisher; and long-tailed tit, Siberian accentor, and Japanese white-eye along with text]

that was a segue into um, the concept of balancing science illustration and, and visual art, because they really are very different disciplines, and so this chapter sort of addresses that, that concept.

Painting the Wall of Birds required balancing two very different disciplines, scientific illustration and fine art. Scientific illustration is data driven and designed to inform, educate and simplify complex processes. And when I’m creating scientific illustrations, I focus on how I want the audience to perceive and interpret the work. I’m hoping to illicit a specific reaction and understanding, so in that sense, the Wall of Birds was one giant scientific illustration. Our goal was to tell a story celebrating the diversity and evolution of birds by showcasing the animals at life-size within their range and natural positions and plumage.

The artistic parameters were rigid and the message was targeted. Fine art on the other hand is an internal process, consideration of the audience is secondary to bringing my artistic vision to life. Rarely do I create a work of fine art with the desire to drive the viewer to a singular conclusion. On the contrary, the best fine art presents a host of philosophical paths for the curious mind to wander. Scientific illustration delivers a lesson, fine art inspires reflection.

So to create a successful mural, I had to find an equilibrium. Fidelity to accuracy was essential, but if that became the soul focus, the mural would run the risk of becoming too dry, too academic, and fundamentally ineffective. But neither was this the place to channel Frida Kahlo.

So there were a number of ways that I had an opportunity to, to interpret. And, to create, make decisions that um weren’t necessarily based on whether or not the audience was going to, to see those decisions or not.

Um I don’t know if any of you have noticed that all of the birds are facing one direction. And then, all of a sudden, they flip. But, it’s actually the Old World and the New World facing each other.

Um and then, at a certain point, right at the edge of the map, they flip back around . And, you know, so you are kind of creating this circular thing, and I love the idea that the kagu is looking across at its closest relative the sunbittern, which is on the opposite side of the world.

So, you know, there are just these small moments like that, that um, if you look at it long enough, you can start to come up with your own questions, and, and your own allegories, and your own metaphors, and um there, I’ll be sharing some of the ones that came to us when we wrote this book.

I’m also going to share just a couple of paintings

[Image: The Innovators painting, two ravens at a nest in a eucalyptus tree with iPhone charging cables woven into the nest]

where you know I think that um, my sweet spot is when just like RGBird, it’s inspired by, by information, or by biology. But, there’s, there is a different metaphor to that. In the case of RGBird, it’s perception. This piece is called The Innovators. Um this was when I was at the de Young, and I wanted to highlight uh native-non-native relationships both in the culture, cultural sense in San Francisco, as we’ve been dealing with some, some interesting economic shifts, and displacement and housing but also, the de Young is set in Golden Gate Park, which of course ecologically has no business being there. It was never meant to be a park as it is today.

But we have a pair of nesting ravens in a non-native eucalyptus tree, and woven into nest are um iPhone lightning cables.

[Laughter]

And really it’s kind of about, you know, just inviting that question of, adaptation um and resilience, you know where, where. And change, you know we all have to learn how to, how to do that.

This piece is called Prime Real Estate.

[Image: Prime Real Estate painting, an Amazon Prime box full of eastern gray squirrels as a California ground squirrel looks on, standing on an 1890s San Francisco real estate map]

And, it is the story of the squirrels that were literally delivered to Golden Gate Park so that we, the residents, had squirrels to feed.

[Laughter]

So these are eastern gray tree squirrels. Of course non-native, um in a prime real estate box, and they are sitting on top of an old 1890s uh real estate map of San Francisco. And the ground squirrel sort of ominously looking at this box of squirrels about to be released on its, on its habitat. And these are just a couple of

[Image: Rise Home painting, various plants connected by a rhizome and insects and a hummingbird nearby]

brand new paintings that I just finished. This piece is called Rise Home, and it’s a play on the word rhizome, and it’s an underground stem that’s connecting a community of plants, and of course it is about interconnectedness, and the importance of that, working together.

This piece is called Cornerstones

[Image: Cornerstones painting, a plant and bird in each of the four corners on a black background]

for two reasons. Recognizing that you know without plants, without all of these beautiful photosynthetic organisms, you know we don’t have a foundation to even have amazing animals. And people. And of course, birds, one of the things that I love hearing so much here at the Lab, was that birds are an indicator species. And so kind of combining these cornerstones was a beautiful marriage, and so this painting you can sort of hang at any corner.

Um this is called Daughter.

[Image: Daughter painting, wood strawberry plant growing off mother plant with silhouette of a plant in the background]

And that little sort of offshoot that you see growing off of the straw, wood strawberry, that’s called a daughter plant. The main plant is a mother, and it sort of puts out these runners or stolons, and they make clones of each other. But, it also, you know that shape, just the silhouette of that plant looked so fallopian to me [laughs]. So kind of creating this uh, mirror image of um, that is meant to evoke thoughts of the female reproductive system.

Okay, so then our

[Image: Pages from the book with heading “Ladies’ Choice” and paintings of the cape sugarbird, cuckoo-roller, and Schlegel’s asity with text]

stories that kind of came into mind about what kind of lessons that we can learn from birds, I’d like to share this excerpt called, well, parts of it, it’s kind of a long one, but I’ll read just a few passages from it.

Um it’s called Ladies’ Choice. And one of the things when I was painting the, the mural, obviously I was painting a lot of male birds. You know, they are the showier versions, they’re the ones that we we recognize first and foremost. They are the displayers when, when mating. But, it kind of got a little bit irritating, and so,

[Laughter]

there were some moments where I had, I had the ability to, to paint the female birds. So I thought I had this bookmarked. Okay.

The lack of female representation in the mural led me to reflect on female representation in ornithological art. To what should be the surprise of no one, women have historically been underrepresented in the field. Some of the earliest western studies of nature come from ancient Greece and Rome, patriarchies in which Aristotle and Pliny the Elder respectively produced writings and descriptions of the natural world that influenced scientists for centuries, but where women had few rights or opportunities.

A role call of the most influential bird artists from the age of exploration to the modern era, John James Audubon, Louis Agassiz Fuertes, Edward Lear, Francis Lee Jaques, Roger Tory Peterson, Charlie Harper, David Sibley to name but a few is similarly devoid of women.

Since the federal duck stamp contest, art contest, the only juried art contest sponsored by the U.S. government, and one which I have had the privilege and honor to judge, held its first public competition in 1949, just three women have won.

You know, and I have to just kind of add a caveat to that. The way that they judge is really quite, quite fair. So you know that’s not necessarily um a remark on that. But when women have advanced, their work has often been overlooked.

The 19th century British artist, naturalist, and entrepreneur John Gould is considered the father of Australian ornithology for his pioneering lithographs of the continent’s birds and wildlife. Yet Gould was not a strong painter. His talents rather lay in making quick field sketches that captured the character of his subject. Overseeing as creative director a team of artists produce his work and in salesmanship, he was a visionary and a scientist, but no artistic genius.

By comparison, Gould’s wife Elizabeth was enormously talented, first in drawing, watercolors, and lithography. In addition to giving birth to their eight children—she died following complications of her last labor—she produced some 600 illustrations for John’s books during their 12 years of marriage. Her initials alongside her husband’s appear on the plates she produced. But it is John who won the applause of history.

So, she actually was the one who painted his lithographs.

Um, Audubon’s skill is indisputable, but the world may never have known his work were it not for the professional discipline and personal sacrifice of his wife Lucy, as both the family’s primary caregiver and breadwinner. Lucy raised their two sons while her husband, financed by her schoolteacher salary, chased birds across the wilds of America for months

[Laughter]

and years at a time. And in publishing Birds of America Lucy acted as an editor, sales woman, and production manager. She even played an influential role in the environmental legacy attached to the Audubon name today.

As a young student, George Bird Grinnell, the founder of Audubon Society of New York, the precursor to today’s national society, grew familiar with the great artist’s work while studying in the home of his tutor Lucy Audubon.

So, you know, I think that, you know 50 years ago, as the daughter of Korean immigrants, I probably wouldn’t have had this opportunity to create, to create this work. Um but there—and, and obviously, more and more women are, are coming into the field, and so many of our Bartels illustrators are often women. So, it, it’s all moving in a wonderful direction. But there’s still so much work to be done, done.

So I hope that the Wall of Birds will stand as an example of the power of female self-determination, and the beauty it can add to the world.

And we kind of came across this story because, we actually started thinking about sexual selection. And really starting to think about well, why is it that all these wonderful male birds have these showy, beautiful characteristics and the songs? And, and it’s really because the females were choosing those genes to then get passed down.

So it’s, it’s this really remarkable story, allegory that you can see in sexual selection, and just the value of what we, each sex brings to [laughs] the world.

Um, I’m gonna share another passage

[Image: Pages from the book with heading “Painting a Song” and paintings of paradise tanager, long-billed woodcreeper, and black-capped donacobius with text]

called Painting a Song.

[Slideshow goes through several slides and ends]

Oops, sorry about that. Bear with me. Technical blip.

[Slideshow is restarted and previous slides are quickly clicked through]

Here we go again, deja vu.

[Low laughter]

Here we go.

Okay. Painting a song, birds are the Broadway stars of the animal kingdom. They flaunt beautiful costumes, perform showy dance routines, and serenade each other in a complexity scientists are only beginning to understand. They sing to announce themselves, warn off threats and rivals, and woo paramours. Their language fills the air with music, birds don’t just communicate, they perform. The neotropics, with all their diversity, provided a grand stage on which to explore the behaviors of avian song and dance.

The first challenge I faced in doing so was a conceptual one. How do you make the audible visible? How do you paint bird song? Simply composing a bird with an open beak doesn’t do the trick, and for the black-capped donacobius singing is a full bodied affair. It bobs up and down in song while wagging its fanned tail feathers, pairing its vocal performance with the physical one. Mated pairs duet either to each other, or in response to other performing couples.

Usually they’ll position themselves one above the other, so I perched this donacobius at an angle about, above an imagined mate. They sing acro—asynchronously in a piercing medley of whirrs and whistles.

Um and that actually, was inspired by um, sort of the late nights that I did keep at the Lab. And um, I kept late hours at the Lab, painting these neotropical birds. And the noises of nature filled my nights. The visitor center stands in Sapsucker Woods Sanctuary, 220 acres of mixed deciduous forests and wetlands.

Sapsucker shelters a classic swath of northeastern wildlife—beavers, birds, coyotes, even the occasional fisher. And outdoor microphones pipe ambient sound into the observatory. I paint in the lift for hours and hours, oblivious to the passing time, while the caterwauling calls of a barred owl like a giant squeegee being dragged across a window

[Laughter]

echoed through the lobby and interrupted my reverie. And during the too frequent all nighters the rolling trill of red-winged blackbirds announcing the dawn informed me it was time to retire.

The chorus often brought to mind the words of Claude Monet. I would like to paint the way a bird sings. On my walk to the car through the sharp morning air I couldn’t help wishing I could sing like them too.

And actually another one of my favorite late night moments, was in July um when the fireflies were out. I felt like I was uh, drunk or something like it was walking through that. And just all of the blinking lights, it was, it was amazing. So yeah, night was a really special time to work at the Lab.

Um this is another one of my favorite

[Slide text: Chapter 7 North America

The American Dream; Image: North American section of Wall of Birds]

allegorical excerpts. Um in, in, the chapters are organized by geographic regions. And so when thinking about North America, what makes North American birds unique? And talking to Fitz, you know he said well, they’re known for their long distance migration. And so wow, that was such a beautiful way to tell um this particular story. So this chapter’s called The American Dream.

They flock to America, year after year, the tired, the poor, and the huddled masses yearning to breathe free. They come by the hundreds, thousands, millions, billions like countless weary travelers before them drawn by the promise of a productive life. Filled with an appetite for hard work, they hope that their offspring will thrive in a land of opportunity. They cross the great seaways of the Pacific and, and Atlantic, past the glowing torch of Lady Liberty whose bronze-cast sonnet “The New Colossus” welcomes “the homeless tempest tost.”

They brave violent Caribbean storms and harsh deserts of Mexico, many of them dying of exhaustion or by the will of those who would wish them harm. They are our country’s original immigrants, the birds of North America. We celebrate some of the continent’s most iconic birds as American, but many of them spend only a few months per year within our country’s borders.

Some 350 of the 650 species that breed here are long distance migrators. They flee the fierce competition of their wintering grounds in Central and South America for the northern spring and its bounty of food and nesting grounds. They understood America as a drive through, long before it became a fast food nation.

[Laughter]

[Image: Page from the book with American white pelican painting and range map along with text]

So I threw in the, that map. I just love you know we chose the American pelican, the white American pelican, as the bird to be paired with this, with this excerpt, but yeah, man, it is truly an American bird.

So I’m just going to end

[Image: Page from the book with heading “Farewell to an Old Friend” and the legs and lower body of the great blue heron painting with text]

um, tonight’s talk before we take questions with this last chapter. And I have to thank the Lab too, once again for regaling more specific stories with me. In order to sort of round out this whole thing.

So Farewell to an Old Friend. The Ornithological artists of yore faced a daunting task long before their brushes ever hit the canvas. In order to accurately paint a bird, they had to observe it first. Sometimes they relied on stuffed specimens to inform their paintings, but the Audubons and Goulds of the world also spent years of their lives in the wilderness and often sailing across vast oceans to get there.

So they, so that they might accurately capture a bird’s spirit and structure. In that context, I had a significantly easier charge. I had seen comparatively few of the mural’s birds in the wild, but with an endless library of photos and videos and the guidance of the world’s best ornithologists I had plenty of great references. There were some birds, however, that I knew on a personal level, including one of the largest and last I painted, the great blue heron.

In 2010, I was accepted to a science illustration internship at the Lab, which was when I first met Fitz and learned of his vision for a mural. I’d arrived expecting to be shuffled into some cramped corner of a dark basement that no one ever visits, as is so often the fate of interns everywhere.

[Laughter]

So I was so surprised and thrilled when I was given a corner desk in the Lab’s large, beautifully lit second floor staff lounge, which sadly does not exist any longer.

[Laughter]

Um the surprises I’d soon discover had just begun. The lounge overlooks Sapsucker Woods Pond, part of the small but thriving wetland network where dam-building beavers shape the landscape, an abundance of fish and frogs attracts a menagerie of birds and other wildlife. The lounge’s long external wall was lined with windows, which were in turn lined with spotting scopes and binoculars that the staff would use to watch the action outside.

The spring of 2010 was a particularly active time both in the lounge and on the pond. A pair of great blue herons took residence in a 50 foot tall dead white oak tree smack in the middle of the pond. And their arrival the year prior marked the first time in recorded history that a pair of great blue herons had nested in Sapsucker Woods.

It was all unfolding in plain view of the offices, and I had literally a front row seat to the action.

The nest four feet wide, one foot deep was a work of art. A delicate sculpture of dead branches woven to shelter new life. All day dozens of Lab staffers would recycle—would cycle in and out of the lounge marveling as all four chicks eventually fledged. Life and death drama unfolded outside my window on a daily basis. During one particularly brutal thunderstorm the male stood atop the nest spreading its six foot wingspan to shelter the mother and the chicks from the elements. To the chagrin of the adults a second breeding pair showed up, building a nest in another tree and ultimately fledged a pair of chicks.

There was hope around the Lab that the pond might become a heronry, but the first pair made very clear that visitors were unwelcome,

[Laughter]

constantly harassing the newcomers. I left the Lab at the end of my five month internship, and the herons soon followed suit. But like me, they would return. The next year the first mating pair came back, and immediately dismantled the second pair’s nest,

[Laughter]

taking the sticks to fortify their own nest. Eventually, the Lab mounted a pair of cameras in the nest. This is an event that deserved to be shared with the world. The herons became an internet sensation. Millions of people watched the lives of these birds unfold with an intimacy never experienced before.

One season while incubating her eggs in the dark of night, the female was attacked by a great horned owl, which resulted in an egg cracking. Fortunately it was not a fatal blow, and as with the other four eggs the chick hatched and fledged. A few months before I returned to the Lab in 2014 to start the mural, a fierce March storm blew the nest apart.

While great blue herons still regularly visit the pond, they no longer nest there. They range across Central and North America, but when it came time for me to paint one on the wall there was never a doubt that I would place it over Sapsucker Woods. Painting this heron felt like revisiting an old friend. I composed it at, as if it were stalking the shallows of Sapsucker Pond waiting for a fish. A gentle breeze has blown its head feathers aflutter, a graceful compositional counterweight to its S, to its sharp and hefty beak. The bird’s blue-gray body is the color of Ithaca’s moody spring sky.

[Laughter]

It’s sweeping shapes, that long S-curve neck, and those stringy chest and back feathers that help it shed the muck that comes with the life in the wetlands, made me feel as if my brush was sculpting the bird rather than painting it.

During those months of my internship I grew to know the great blue heron as patient, disciplined, and extremely fast when the situation demanded.

[Laughter]

Lessons that I drew to complete this mural. I painted the great blue heron as a celebration of the time nesting at the pond, and as an invitation for them to soon return.

So, it is an honor and a privilege uh to share the Wall of Birds with you and the world, and more so this book, which really is meant to be read. So I hope that you all have enjoyed some of the excerpts that I shared with you tonight.

Thank you so much again for coming. It really is truly a pleasure to be back here.

[Applause]

[Slide text: THANK YOU

www.inkdwell.com

CONTACT: info@inkdwell.com

Instagram + Twitter: @inkdwell

Facebook: www.facebook.com/inkdwell

INKDWELL]

So I’m more than happy to take questions.

[Kevin] Yeah, we have time for questions. Let me get [inaudible] turn the house lights up.

[Pause]

[Jane] Yes.

[Audience] Hi.

[Jane] Hi.

[Audience] Thank you for that lecture, it was marvelous. And I’m just, I’m really eager to ask you, a couple of years ago when the mural was first open to us I was upstairs looking at it, and the, this has never happened to me before, I, I was smitten by one of the birds.

[Jane] Ohh.

[Audience] And I’d love to know if you or anyone else has any story about how you chose the shoebill in Africa.

[Jane] So the question is uh how did we choose the shoebill in Africa, and I believe the answer to that is that’s it’s the only one in its family. So, some of those, um, that was not a task that I had. I’m very grateful for that, actually.

[Laughter]

The Lab had to come up with the final master list, and, and for a bird like that it was very easy. But some of other birds um required a lot more, more discussion.

[Audience] How did you get the model for it? [Inaudible] I mean, I guess you used photographs, but

[Jane] Well, actually, the second part of that question was, what were the references that I used for that? The Lab actually has a taxidermy shoebill. So I had the great fortune to actually see it stuffed and mounted, not just in a drawer. Um but of course watching, I do a lot of—I watch a lot of videos. Um because, you know, there really is nothing like being able to see the birds in person, and in the wild. And of course I am not even close to being able to see these birds. But videos really do help me understand um their behavior. And kind of pausing and capturing stills, and then of course, collecting photographs.

[Audience] You did a wonderful job with that one.

[Jane] Oh, thank you.

[Audience] I mean all of them, but that one in particular just kind of jumped out.

[Jane] Thank you, I appreciate that. Any other questions? Yes?

[Audience] Um, thank you. And um I want to applaud your commitment to public art, which is, you know, enriches us all.

[Jane] Oh, thank you very much.

[Audience] Thank you. Um, as someone whose artistic talent is kind of in Kevin’s range of stick figures,

[Jane laughs]

um and as someone who can barely write a few sentences without a whoops somewhere along the line,

[Jane] Yeah [laughs].

[Audience] when you’re doing a mural like this, do you have any whoops moments, and

[Laughter]

if you do,

[Jane laughs]

what do you do next? How do you handle that?

[Jane] So the question was what happens when I make a mistake, which—and of course, inevitably I do, um the cool thing about paint is you can cover it up.

[Laughter]

No, but really, it’s um, the lift is shaky. You know, you just sort of get used to that motion of uh rocking back and forth. Uh, but sometimes honestly painting feels like you’re just pushing paint around until you get it to where you like it.

[Laughter]

So I don’t know how to better describe that. And there were some birds that were really a struggle. Ones that I thought were going to be much easier than they were but ended up really kicking my butt. Um, you know the ostrich was one of those birds.

I had this insane spreadsheet. Um it was not beautiful or romantic whatsoever. It was just an Excel spreadsheet of birds that I put next to it, a time slot of okay I’m gonna give this bird six hours. I’m gonna give this bird five days. I’m gonna give this one three days. Um I had allotted seven days for that ostrich and it took, five days for the ostrich and it took seven. So that was actually really stressful because it was one of the earliest birds that I had painted.

But you just eventually, find a place where you say, okay, I can move on. But, you know, I’m not, I definitely have birds there that, I didn’t know—are you all familiar with the interactive that was created? Um by Bird Academy. So fabulous. I didn’t know that was gonna be made um beforehand, and you can zoom in to every single one of the birds.

[Laughter]

In way more detail than I ever expected.

[Laughter]

So there are ones that you know are higher up and I thought well no one is really going to see this one.

[Laughter]

[Jane laughs] But that wasn’t the case at all. But yeah, there are birds that I feel are better than others. Clearly my cover bird the great hornbill was one of my favorites and still remains today as one of my favorites.

[Audience] Jane thank you, first of all. Um, I’m just curious what, you know, you release your art to the world, it becomes bigger than even the experience of making um, because you share the experience with others, and you’ve had so many steps along the way since it was completed, and now you’re back tonight. Um, how does it feel to be back tonight to see it and see how it’s affecting people?

[Jane] So how does it feel to be back tonight after all this time of creating the work. It feels great! [Laughs]

[Laughter]

[Jane] I can’t tell you, it’s just such a joyful moment for me to be back, and to see the work on the wall. You know, once you paint it, and you leave it, and with public art, it’s no longer yours. So how the public continues to perceive the work, or the meaning that it will continue to have for that community, is it—you no longer own that. But I, have so much, so many proud moments and feelings knowing that this mural will continue to be used and, and enjoyed, and, and experienced, and as a learning tool, just something to visually enjoy.

Actually, I’m just gonna point out, Emma Regnier, she was actually one of the assistants that helped with the mural. She’s a student here at Cornell. And she was just letting me know that, just last term they had to study the families, bird families of the world. You know, they would just come out and look at the wall and, and quiz each other, and learn from that. And gosh, that’s the kind of stuff that I hope to continue to hear.

But mostly, it is just, I’m almost outside of it. Like, wow, who painted that [laughs].

[Laughter]

Yeah. It’s kind of hard to imagine. Yep?

[Audience] What was the last bird you painted, and how did it feel to be in the final moments?

[Jane] Yeah. That’s a great question. Thank you. What was the last bird that I painted, and what did that feel like? Um, the last bird that I painted was the barn owl. The first bird that I painted was the New Zealand saddleback. But when I fi—finished the, the barn owl, you know it should have felt like a celebratory moment. But that also marked the beginning of having to paint the evolution.

So, the evolution, I didn’t even read any excerpts from that. Um most of the excerpts are actually quite technical. But it felt like two completely separate murals. So that ended, and I was like, okay, now I gotta go do this [laughs].

And then I have another sort of funny story to share that even when I finished the evolution, that’s when we started rolling out sort of the publicity of the work, and it started to hit media. And I don’t, I think it might have been in Audubon, a blog, you know an online news story in Audubon. And we got an email from a reader, who had said, oh, I love this project but I just—I feel badly about saying this, but, the great gray owl’s tail is painted backwards.

[Laughter]

And, it was one of the first birds that I had painted. Um, and, you know, this is an institution of ornithological study

[Laughter]

and no one caught it! It was kind of funny. And, and totally embarrassing. But, I had to go back and fix that tail,

[Laughter]

so you know, um I actually do this so often, and it really irritates me, but when I’m painting bird tail feathers in flight, you know, looking at the ventral side, I often flip it like I’m looking at it on the top side. And um, the way that birds’ feather lay, it’s very specific in how they overlap, so it was wrong [laughs].

[Laughter]

And I had to go back and repaint that. So, yeah, there were a lot of funny moments. So that, that’s kind of a mistake question there.

[Laughter]

Yeah, yeah. Yes?

[Audience] Okay, my favorite bird is the magnificent frigatebird.

[Jane] Oh, cool.

[Audience] I want you to talk a little bit about how it won that prestigious position.

[Jane laughs]

[Audience] Over the sprinkler.

[Jane] Great, yes. The question is around the uh magnificent frigatebird and how I chose its posture and location on the wall. So, actually, you know, I’m gonna kind of flip back, because, you know that doesn’t mean that there weren’t some deviations. So I want to refer back to the original concept sketch.

So I had initially envisioned

[Image: Original concept sketch for the mural with the frigatebird in flight over the door between South America and Africa]

the frigatebird in flight. But I really wanted to show off that red pouch, and when I did my very first preliminary sketch, I was informed that they wouldn’t ever really display the pouch like that in flight. I thought, well, what am I going to do? It’s an ocean bird, so I have to figure out some place for it.

And then, I just looked up where I was going to paint it, and noticed that there was a sprinkler, a fire,

[Laughter]

you know, sprinkler above the doorway and I thought, well, there’s a perch, that’s perfect!

[Laughter]

So, that is how I landed on uh the location and the position of the bird.

[Laughter]

Any other questions? Yes?

[Audience] What was the hardest bird to paint, and why?

[Jane] Oooh. What was the hardest bird to paint and why? Hmmm. They were all hard on some level. Um I think the wandering albatross was one that I went through more iterations than any of the others. And I don’t know if it’s its proportions or what have you, but um, as you can see, most of the renderings that I did were on a small scale.

[Photo: Several final drawings of birds and a hornbill skull on a table]

They were about, you know, nine by twelve inches. But the wandering albatross when I created it small, and then scanned it and it blew it up, it just always looked wrong to me. And, um I tried it several times, and it always just looked off. So I ended up having to just draw the wandering albatross at scale.

So I drew it with—at that scale, and then transferred that directly to the wall. So um that, that definitely was one of the more challenging ones. Um, let’s see, what other birds? Hmm hmm hmm. Yeah, that ostrich like I said was quite difficult. Um, you know the penguin was kind of a tricky one. The emperor penguin. Um I didn’t want it to kind of just feel like a black silhouette, but I also didn’t quite have the time to spend on rendering every single one of those tiny, tiny, tiny feathers.

So, um I think the challenge, one of the things, there is actually an excerpt in the book that addresses this is, um, I had to find techniques that would yield the highest results in the fewest brush strokes. Um, so how to capture a lot of detail, or the suggestion of detail, but then also having to paint the birds in a lot of high contrast. You know I might not actually paint in the same way, um, you know I’m just going to go ahead—like this for example. You know, the way that I painted these crow—uh these ravens.

[Image: The Innovators painting, two ravens at a nest in a eucalyptus tree with iPhone charging cables woven into the nest]

Um, you know when they’re meant to be just looked here, this is just a different approach. Um a lot of the birds on the wall you’ll notice have a very high contrast graphic quality. Um I was painting the, the cassowary, and it was at, late at night, and it gets quite dim. And I’m working really hard on that head. Putting a lot of love and attention and detail. And I come down from the lift, and go upstairs to that second floor landing and I look, and I’m like, I can’t see a thing that I painted!

Um so, you know, it was really telling that, just the approach that I had to take for suggesting feathers or, highlights, you know, really had to come with a lot of contrast.

Any other questions? Yes?

[Audience] How did you decide how many birds you would depict in a geographic area?

[Jane] Oh, that’s a great question. How, uh, how did we lay the birds on the map? Um, we did want to round out the whole map as best as we could. So, you know some of the birds like the peregrine falcon that could be found worldwide, we sort of filled in those places in the Middle East where there might not have been as many sort of endemic families, or just, yeah. So we chose the great tit, for example, you know is probably more familiar as a European sort of bird, but we put it in China.

Um, and, oh, I had to go back and repaint that one too, because we discovered later that the yellow sort of sides, flanks on a great tit is more common for Europe and not China. So we had to sort of white that out a little more to, to make it appropriate for that region. So there were a lot of these fun things. And, funny enough, this mural is already out of date. I think that there are several new bird families that have been added to the list since, since this mural was finished. And, actually, when we first started the mural, there were like 12 less families, so, even in the time that I was painting the murals, the number of families grew. So.

[Kevin] We just kept looking at that as a reason to bring you back.

[Laughter]

[Jane] That’s what I was hoping someone would say [laughs].

[Kevin] Jane has to come back and paint another one.

[Jane] Yeah, let’s make it a every ten year thing thing [laughs].

[Laughter]

Well, thank you so much.

[Kevin] Thank you so much, Jane. And you are gonna sign books?

[Jane] Yes, I would love to.

[Kevin] So book signing afterwards, thank you very much.

[Applause]

[Jane] Thank you. Thanks for coming.

[Applause]

End of transcript

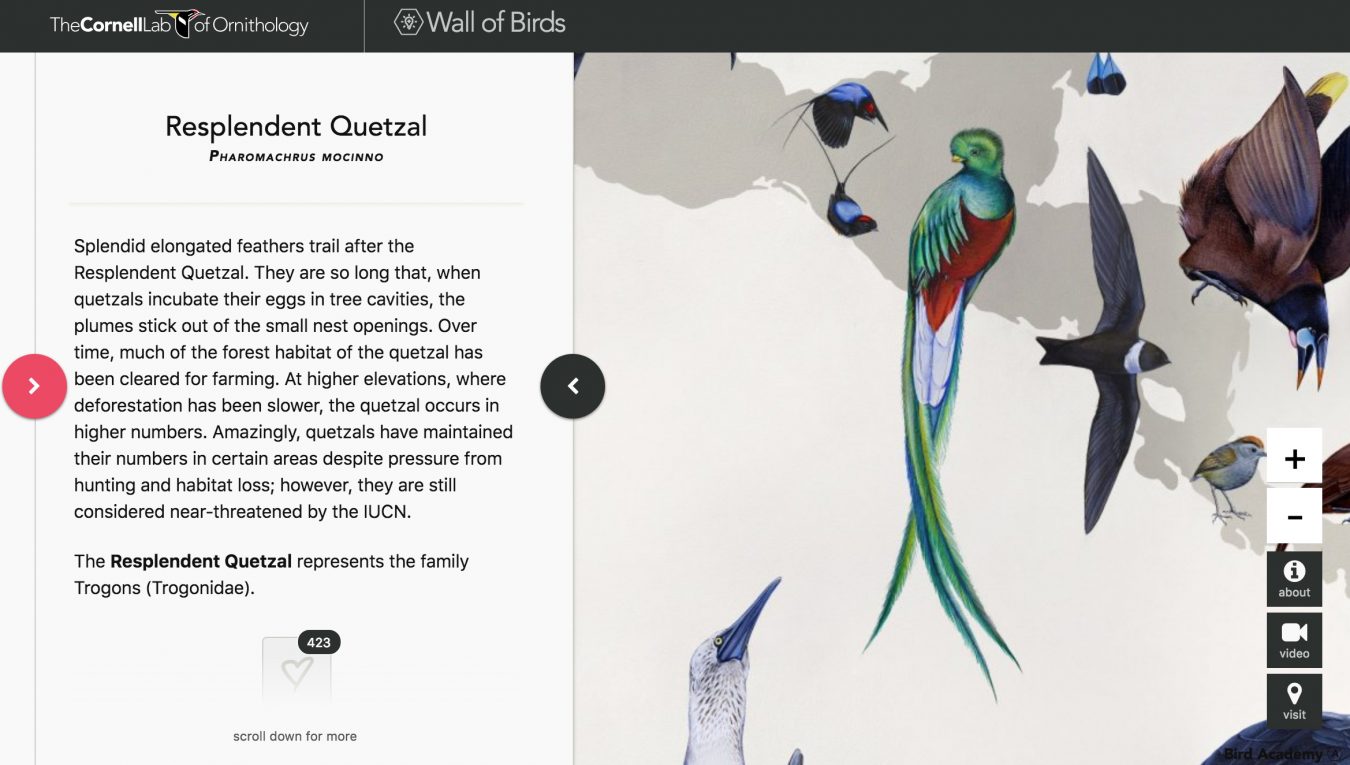

Celebrate the diversity and evolution of birds with artist Jane Kim, who brought to life the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s magnificent 2,500-square-foot Wall of Birds mural. Part homage, part artistic and sociological journey, The Wall of Birds tells the story of birds’ remarkable 375-million-year evolution. In this talk, Kim will discuss her new book about the project, The Wall of Birds, exploring the intersection of art and natural history, the creative process, and surprising lessons that we humans can learn from birds.

You can explore the Lab’s interactive version of the epic mural anytime: Wall of Birds