Mary

Forum Replies Created

Viewing 6 posts - 1 through 6 (of 6 total)

-

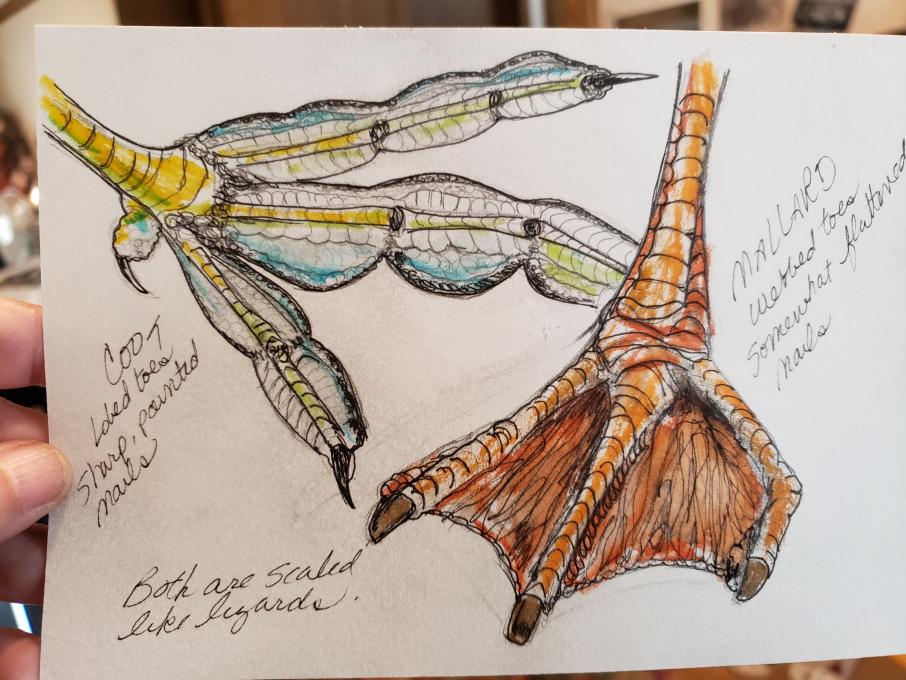

MaryParticipantI did my comparison study on the feet of American Coots and Mallard ducks. Coots have lobed toes and very sharp toenails; Mallards have webbed feet and somewhat flat toenails. Coots legs and feet are a mix of blue gray, green, and yellow; Mallard feet and legs are various shades of orange and umber. The toe formation, webbing variance and different colors made me wonder why the birds were put together like that.

The Coots are more or less confined to marsh lands. Their lobed toes give them traction in the water when they’re swimming, but the separation between the toes also allows for more flexibility on land and walking through and over matts of marsh plants. The Coots also use their feet in dominance battles. I would assume that the light color of their legs and feet make it less likely that predators under the water could see them, and might mistake them for wafting plant frond. On land, they WALK rather than WADDLE.

I know that Mallards are the ancestors of all of the domestic duck (except the Muscovy) and they can thrive in a variety of habitats. Although they nest on ground, they spend a lot of time in the water feeding and displaying to one another. Obviously, their webbed feet make it easier to maneuver in the water while still allowing them to travel on land. The orange color, though, is suddenly interesting to me. Why such a bright and obvious color on their feet? I did a little more research on them and discovered that the color of their feet can vary depending on their age and hormone levels. The feet turn bright orange in the breeding season, signaling to others that they’re old enough and healthy enough to breed. On land, the ducks WADDLE rather than WALK. in reply to: The Power of Comparison #666219

The Coots are more or less confined to marsh lands. Their lobed toes give them traction in the water when they’re swimming, but the separation between the toes also allows for more flexibility on land and walking through and over matts of marsh plants. The Coots also use their feet in dominance battles. I would assume that the light color of their legs and feet make it less likely that predators under the water could see them, and might mistake them for wafting plant frond. On land, they WALK rather than WADDLE.

I know that Mallards are the ancestors of all of the domestic duck (except the Muscovy) and they can thrive in a variety of habitats. Although they nest on ground, they spend a lot of time in the water feeding and displaying to one another. Obviously, their webbed feet make it easier to maneuver in the water while still allowing them to travel on land. The orange color, though, is suddenly interesting to me. Why such a bright and obvious color on their feet? I did a little more research on them and discovered that the color of their feet can vary depending on their age and hormone levels. The feet turn bright orange in the breeding season, signaling to others that they’re old enough and healthy enough to breed. On land, the ducks WADDLE rather than WALK. in reply to: The Power of Comparison #666219 -

MaryParticipantMy friend Roxanne and I are always trying to learn from what we see and ask ourselves questions about forms and functions. I’ve been focusing a lot on lichen lately, and have begun to observe the different ways the lichen reproduce. Some use apothecia through which they produce and release spores, some use soredia (crumbly-looking bundles of algae and fungus cells that they shed – which then go on to form another lichen), some use isidia (structures that look like eyelashes on the edges of the lichen)… and some use a combination of those structures. I used to think of lichen as fairly “commonplace” somewhat “simple” structures, but observation has shown me how complex and varied they are. I’ve been using a macro attachment for my cellphone to observe some of the deeper details and structures of lichen. Here’s an example of what Bark Rim Lichen, Lecanora chlarotera looks like to the naked eye and to the macro attachment:

To the naked eye,the lichen looks like white-wash on the bark. But using the macro attachment, I was able to observe the apothecia (cup-like structures used for spore formation) all over the lichen's surface.

To the naked eye,the lichen looks like white-wash on the bark. But using the macro attachment, I was able to observe the apothecia (cup-like structures used for spore formation) all over the lichen's surface.

in reply to: Noticing Themes in Nature #666178

in reply to: Noticing Themes in Nature #666178 -

MaryParticipant

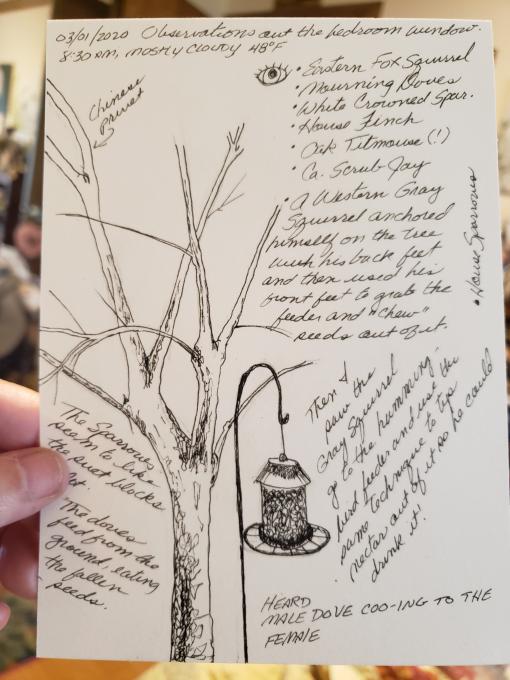

[[I was more focused on observing and taking notes than drawing, so my drawing for today isn’t very detailed.]]

I had just filled the birdfeeder outside my bedroom window, and watched the birds and squirrels that came to it. I drew the Chinese Privet tree and the feeder, but also used my cellphone camera to get some images.

I saw White-Crowned Sparrows, Mourning Doves, a California Scrub Jay, House Finches, House Sparrows and an Oak Titmouse. There was also a young Eastern Fox Squirrel who couldn’t quite figure out how to get the seeds in the feeder, and an adult Western Gray Squirrel who was adept at stealing the seeds. That squirrel also went over to the hummingbird feeder and tipped it just enough to get the nectar inside to dribble out, and he drank from the feeder! Ingenious!

[[I was more focused on observing and taking notes than drawing, so my drawing for today isn’t very detailed.]]

I had just filled the birdfeeder outside my bedroom window, and watched the birds and squirrels that came to it. I drew the Chinese Privet tree and the feeder, but also used my cellphone camera to get some images.

I saw White-Crowned Sparrows, Mourning Doves, a California Scrub Jay, House Finches, House Sparrows and an Oak Titmouse. There was also a young Eastern Fox Squirrel who couldn’t quite figure out how to get the seeds in the feeder, and an adult Western Gray Squirrel who was adept at stealing the seeds. That squirrel also went over to the hummingbird feeder and tipped it just enough to get the nectar inside to dribble out, and he drank from the feeder! Ingenious!

I could hear the squirrels running across the roof, to and from the feeders. When the squirrels were around, the birds stayed back from the feeders but didn’t fly away.

I could hear the sparrows “chirp” at each other, and heard the male Mourning Dove cooing to the female as he followed closely after her along the ground. She didn’t seem interested in him and kept avoiding his attentions by scurrying away. I could hear the wind whistling through the doves’ tail feathers when they flew in and flew out.

The White-Crowned Sparrows were more interested in the suet blocks than the seeds in the feeder, and the doves ate the seeds that fell onto the ground. Some of the White-Crowns ate seeds off the ground, too; they kept looking up and around them every few seconds as they fed. Keeping an eye out for other birds and predators? Some of the White-Crowns also flit up onto the window sill to peck up the seeds there. They’d look up into the window as they fed.

I could hear the squirrels running across the roof, to and from the feeders. When the squirrels were around, the birds stayed back from the feeders but didn’t fly away.

I could hear the sparrows “chirp” at each other, and heard the male Mourning Dove cooing to the female as he followed closely after her along the ground. She didn’t seem interested in him and kept avoiding his attentions by scurrying away. I could hear the wind whistling through the doves’ tail feathers when they flew in and flew out.

The White-Crowned Sparrows were more interested in the suet blocks than the seeds in the feeder, and the doves ate the seeds that fell onto the ground. Some of the White-Crowns ate seeds off the ground, too; they kept looking up and around them every few seconds as they fed. Keeping an eye out for other birds and predators? Some of the White-Crowns also flit up onto the window sill to peck up the seeds there. They’d look up into the window as they fed.

Didn’t observe long enough to see “intervals” of movement; but I’m looking forward to doing more observations outside at more remote locations. in reply to: Opening Your Senses #666172

Didn’t observe long enough to see “intervals” of movement; but I’m looking forward to doing more observations outside at more remote locations. in reply to: Opening Your Senses #666172 -

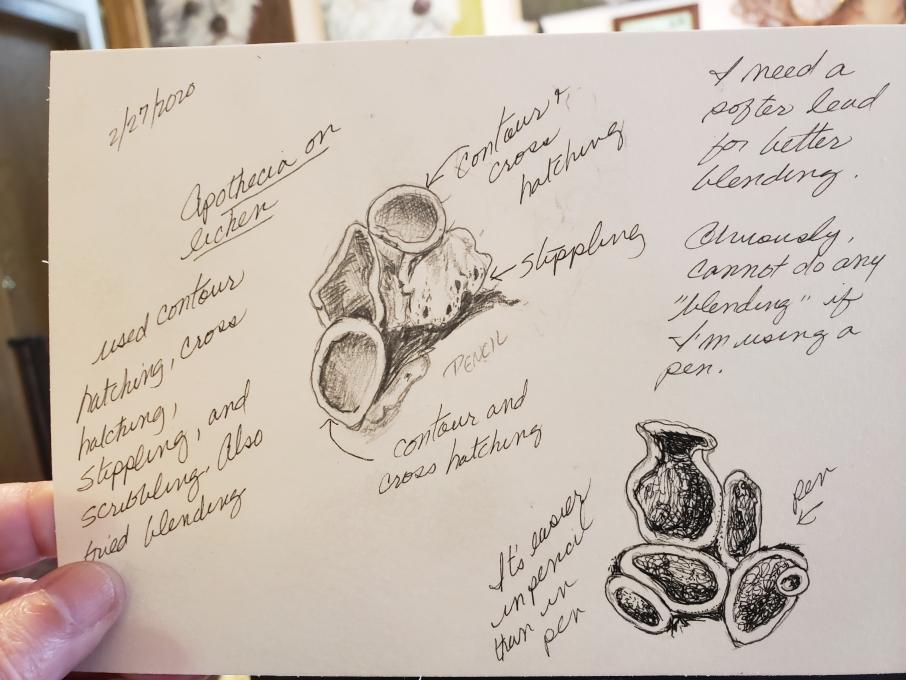

MaryParticipantI used to do all kinds of “pointillism” (stippling) drawings, so I’m familiar with that one, but that takes a LOT of time and concentration, so I can’t see doing that in the field. And for blending, I need a much softer lead in my pencil. So, I ordered some 2B lead and some blending stumps. I tried different techniques with simple shapes, like the apothecia on lichen. I liked using the pencil more than the pen for most of the techniques. I found that I tended to MIX the techniques depending on the density of the shadow and color and the texture of the lichen.

I am feeling a bit more confident about laying down shapes and doing shading, but I know I'll need more work to get comfortable with it in the field. I need more work with fur and feather's too as they seem daunting. Drawing things likes eggs and lichen seem easy in comparison. in reply to: Illustrating the 3D World #665482

I am feeling a bit more confident about laying down shapes and doing shading, but I know I'll need more work to get comfortable with it in the field. I need more work with fur and feather's too as they seem daunting. Drawing things likes eggs and lichen seem easy in comparison. in reply to: Illustrating the 3D World #665482 -

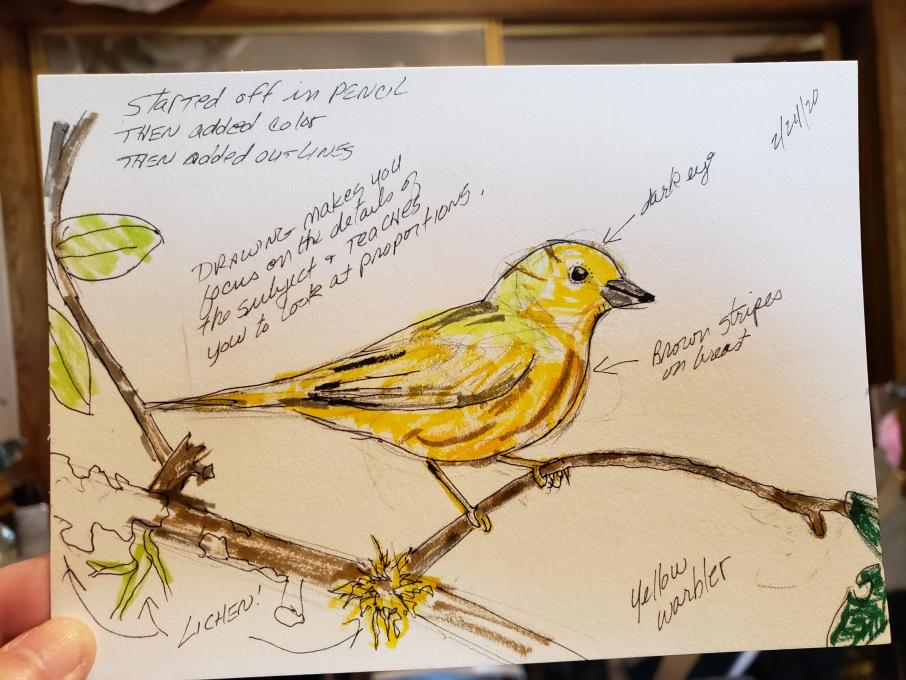

MaryParticipantI started my drawing in pencil, then added splashes of color then outlines things in black. I noticed as I was doing this that I was “distracted” by nagging thoughts about shape and proportion, and I had to dismiss those in order to proceed with the image. As I was working, I was also distracted from the bird by the realization that there were LICHEN on the branch the bird was sitting on. I’m really into lichen right now, so that detail pulled my focus for a while. I think the biggest thing I noticed as I was working was how the bird’s feet were wrapped around the branch. I focused on its toes for a bit, and how the toenails were sooooo long.When I’d finished with the drawing, I added a date and a few notes.

Q: What advantages do drawings have over photos?

Drawing forced me to break the image down into components. I used the technique of creating the bird out of geometric shapes, and that really helped. I don’t think I got the proportions right, but I won’t beat myself up over that.

The “advantage” to drawing is that it made me STOP and really LOOK at the bird: how its body was put together; what its eye color was; what the beak color and shape were; how its feet were holding the branch. I also noticed more about the branch itself; the lichen on in; the gnarly wood; the leaf with the circle cut out of it (probably by a leaf-cutter bee)… I was more “present” with the bird and its surroundings.

If the nature journal is supposed to act, in part, as an assist to scientific understanding and knowledge of wildlife and their habitat, then noticing and capturing the “small stuff” (like the lichen) would be important. It makes me wonder what sort of habitat the Yellow Warblers prefer to live in. Will Climate Change affect them? Do they interact at all with the lichen (for nesting, etc.)? It makes me want to learn a lot more.

Q: What advantages do photos have over drawings?

The most obvious advantage to me is that a photo freeze-frames a particular moment in time, and you can take that image home with you and draw from it (rather than sitting out in the field)

Photos also have the advantage of keeping your subject absolutely still. Birds flit all over the place; trying to do a drawing of a moving subject would make me, as a beginner at nature journaling, absolutely crazy.

Another advantage: The light stays the same. When you’re in the field, even a few minutes can completely change the way the light on your subject looks and acts. in reply to: Jump Right in! #665114

Q: What advantages do drawings have over photos?

Drawing forced me to break the image down into components. I used the technique of creating the bird out of geometric shapes, and that really helped. I don’t think I got the proportions right, but I won’t beat myself up over that.

The “advantage” to drawing is that it made me STOP and really LOOK at the bird: how its body was put together; what its eye color was; what the beak color and shape were; how its feet were holding the branch. I also noticed more about the branch itself; the lichen on in; the gnarly wood; the leaf with the circle cut out of it (probably by a leaf-cutter bee)… I was more “present” with the bird and its surroundings.

If the nature journal is supposed to act, in part, as an assist to scientific understanding and knowledge of wildlife and their habitat, then noticing and capturing the “small stuff” (like the lichen) would be important. It makes me wonder what sort of habitat the Yellow Warblers prefer to live in. Will Climate Change affect them? Do they interact at all with the lichen (for nesting, etc.)? It makes me want to learn a lot more.

Q: What advantages do photos have over drawings?

The most obvious advantage to me is that a photo freeze-frames a particular moment in time, and you can take that image home with you and draw from it (rather than sitting out in the field)

Photos also have the advantage of keeping your subject absolutely still. Birds flit all over the place; trying to do a drawing of a moving subject would make me, as a beginner at nature journaling, absolutely crazy.

Another advantage: The light stays the same. When you’re in the field, even a few minutes can completely change the way the light on your subject looks and acts. in reply to: Jump Right in! #665114 -

MaryParticipantI am a certified California naturalist and I keep a "digital" field journal on my blog (https://chubbywomanwalkabout.com/) with type-written text and photographs. I'm taking this class because I'd like to get more hands-on with my observations, and learn to focus more on details rather than big-picture images. I'm hoping that once I get more comfortable drawing in a journal, I can pass what I learn onto my naturalist students. Hard-bound art journals seem too confining and limiting to me, however, and they can also be bulky and heavy, so I've decided to start with small sheets of watercolor paper that I can carry with me in a pack with some watercolor pens, pencils and permanent markers. That may change as I continue on this journey, but it's where I'll start. I also really liked the verbalized notation in one of the videos that mentioned submitting images drawn in the field to iNaturalist. I thinks that's an awesome idea and a great way to inspire others and let them know that their nature journals are IMPORTANT to science and USEFUL to others. Here is what my current digital journal looks like:

in reply to: Style Your Journal Your Way #665105

in reply to: Style Your Journal Your Way #665105

Viewing 6 posts - 1 through 6 (of 6 total)

The Coots are more or less confined to marsh lands. Their lobed toes give them traction in the water when they’re swimming, but the separation between the toes also allows for more flexibility on land and walking through and over matts of marsh plants. The Coots also use their feet in dominance battles. I would assume that the light color of their legs and feet make it less likely that predators under the water could see them, and might mistake them for wafting plant frond. On land, they WALK rather than WADDLE.

I know that Mallards are the ancestors of all of the domestic duck (except the Muscovy) and they can thrive in a variety of habitats. Although they nest on ground, they spend a lot of time in the water feeding and displaying to one another. Obviously, their webbed feet make it easier to maneuver in the water while still allowing them to travel on land. The orange color, though, is suddenly interesting to me. Why such a bright and obvious color on their feet? I did a little more research on them and discovered that the color of their feet can vary depending on their age and hormone levels. The feet turn bright orange in the breeding season, signaling to others that they’re old enough and healthy enough to breed. On land, the ducks WADDLE rather than WALK.

The Coots are more or less confined to marsh lands. Their lobed toes give them traction in the water when they’re swimming, but the separation between the toes also allows for more flexibility on land and walking through and over matts of marsh plants. The Coots also use their feet in dominance battles. I would assume that the light color of their legs and feet make it less likely that predators under the water could see them, and might mistake them for wafting plant frond. On land, they WALK rather than WADDLE.

I know that Mallards are the ancestors of all of the domestic duck (except the Muscovy) and they can thrive in a variety of habitats. Although they nest on ground, they spend a lot of time in the water feeding and displaying to one another. Obviously, their webbed feet make it easier to maneuver in the water while still allowing them to travel on land. The orange color, though, is suddenly interesting to me. Why such a bright and obvious color on their feet? I did a little more research on them and discovered that the color of their feet can vary depending on their age and hormone levels. The feet turn bright orange in the breeding season, signaling to others that they’re old enough and healthy enough to breed. On land, the ducks WADDLE rather than WALK.  To the naked eye,the lichen looks like white-wash on the bark. But using the macro attachment, I was able to observe the apothecia (cup-like structures used for spore formation) all over the lichen's surface.

To the naked eye,the lichen looks like white-wash on the bark. But using the macro attachment, I was able to observe the apothecia (cup-like structures used for spore formation) all over the lichen's surface.

[[I was more focused on observing and taking notes than drawing, so my drawing for today isn’t very detailed.]]

I had just filled the birdfeeder outside my bedroom window, and watched the birds and squirrels that came to it. I drew the Chinese Privet tree and the feeder, but also used my cellphone camera to get some images.

I saw White-Crowned Sparrows, Mourning Doves, a California Scrub Jay, House Finches, House Sparrows and an Oak Titmouse. There was also a young Eastern Fox Squirrel who couldn’t quite figure out how to get the seeds in the feeder, and an adult Western Gray Squirrel who was adept at stealing the seeds. That squirrel also went over to the hummingbird feeder and tipped it just enough to get the nectar inside to dribble out, and he drank from the feeder! Ingenious!

[[I was more focused on observing and taking notes than drawing, so my drawing for today isn’t very detailed.]]

I had just filled the birdfeeder outside my bedroom window, and watched the birds and squirrels that came to it. I drew the Chinese Privet tree and the feeder, but also used my cellphone camera to get some images.

I saw White-Crowned Sparrows, Mourning Doves, a California Scrub Jay, House Finches, House Sparrows and an Oak Titmouse. There was also a young Eastern Fox Squirrel who couldn’t quite figure out how to get the seeds in the feeder, and an adult Western Gray Squirrel who was adept at stealing the seeds. That squirrel also went over to the hummingbird feeder and tipped it just enough to get the nectar inside to dribble out, and he drank from the feeder! Ingenious!

I could hear the squirrels running across the roof, to and from the feeders. When the squirrels were around, the birds stayed back from the feeders but didn’t fly away.

I could hear the sparrows “chirp” at each other, and heard the male Mourning Dove cooing to the female as he followed closely after her along the ground. She didn’t seem interested in him and kept avoiding his attentions by scurrying away. I could hear the wind whistling through the doves’ tail feathers when they flew in and flew out.

The White-Crowned Sparrows were more interested in the suet blocks than the seeds in the feeder, and the doves ate the seeds that fell onto the ground. Some of the White-Crowns ate seeds off the ground, too; they kept looking up and around them every few seconds as they fed. Keeping an eye out for other birds and predators? Some of the White-Crowns also flit up onto the window sill to peck up the seeds there. They’d look up into the window as they fed.

I could hear the squirrels running across the roof, to and from the feeders. When the squirrels were around, the birds stayed back from the feeders but didn’t fly away.

I could hear the sparrows “chirp” at each other, and heard the male Mourning Dove cooing to the female as he followed closely after her along the ground. She didn’t seem interested in him and kept avoiding his attentions by scurrying away. I could hear the wind whistling through the doves’ tail feathers when they flew in and flew out.

The White-Crowned Sparrows were more interested in the suet blocks than the seeds in the feeder, and the doves ate the seeds that fell onto the ground. Some of the White-Crowns ate seeds off the ground, too; they kept looking up and around them every few seconds as they fed. Keeping an eye out for other birds and predators? Some of the White-Crowns also flit up onto the window sill to peck up the seeds there. They’d look up into the window as they fed.

Didn’t observe long enough to see “intervals” of movement; but I’m looking forward to doing more observations outside at more remote locations.

Didn’t observe long enough to see “intervals” of movement; but I’m looking forward to doing more observations outside at more remote locations.  I am feeling a bit more confident about laying down shapes and doing shading, but I know I'll need more work to get comfortable with it in the field. I need more work with fur and feather's too as they seem daunting. Drawing things likes eggs and lichen seem easy in comparison.

I am feeling a bit more confident about laying down shapes and doing shading, but I know I'll need more work to get comfortable with it in the field. I need more work with fur and feather's too as they seem daunting. Drawing things likes eggs and lichen seem easy in comparison.  Q: What advantages do drawings have over photos?

Drawing forced me to break the image down into components. I used the technique of creating the bird out of geometric shapes, and that really helped. I don’t think I got the proportions right, but I won’t beat myself up over that.

The “advantage” to drawing is that it made me STOP and really LOOK at the bird: how its body was put together; what its eye color was; what the beak color and shape were; how its feet were holding the branch. I also noticed more about the branch itself; the lichen on in; the gnarly wood; the leaf with the circle cut out of it (probably by a leaf-cutter bee)… I was more “present” with the bird and its surroundings.

If the nature journal is supposed to act, in part, as an assist to scientific understanding and knowledge of wildlife and their habitat, then noticing and capturing the “small stuff” (like the lichen) would be important. It makes me wonder what sort of habitat the Yellow Warblers prefer to live in. Will Climate Change affect them? Do they interact at all with the lichen (for nesting, etc.)? It makes me want to learn a lot more.

Q: What advantages do photos have over drawings?

The most obvious advantage to me is that a photo freeze-frames a particular moment in time, and you can take that image home with you and draw from it (rather than sitting out in the field)

Photos also have the advantage of keeping your subject absolutely still. Birds flit all over the place; trying to do a drawing of a moving subject would make me, as a beginner at nature journaling, absolutely crazy.

Another advantage: The light stays the same. When you’re in the field, even a few minutes can completely change the way the light on your subject looks and acts.

Q: What advantages do drawings have over photos?

Drawing forced me to break the image down into components. I used the technique of creating the bird out of geometric shapes, and that really helped. I don’t think I got the proportions right, but I won’t beat myself up over that.

The “advantage” to drawing is that it made me STOP and really LOOK at the bird: how its body was put together; what its eye color was; what the beak color and shape were; how its feet were holding the branch. I also noticed more about the branch itself; the lichen on in; the gnarly wood; the leaf with the circle cut out of it (probably by a leaf-cutter bee)… I was more “present” with the bird and its surroundings.

If the nature journal is supposed to act, in part, as an assist to scientific understanding and knowledge of wildlife and their habitat, then noticing and capturing the “small stuff” (like the lichen) would be important. It makes me wonder what sort of habitat the Yellow Warblers prefer to live in. Will Climate Change affect them? Do they interact at all with the lichen (for nesting, etc.)? It makes me want to learn a lot more.

Q: What advantages do photos have over drawings?

The most obvious advantage to me is that a photo freeze-frames a particular moment in time, and you can take that image home with you and draw from it (rather than sitting out in the field)

Photos also have the advantage of keeping your subject absolutely still. Birds flit all over the place; trying to do a drawing of a moving subject would make me, as a beginner at nature journaling, absolutely crazy.

Another advantage: The light stays the same. When you’re in the field, even a few minutes can completely change the way the light on your subject looks and acts.